All the king’s horses and all the king’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again

Humpty Dumpty, English Nursery Rhyme

“Can you please just tell me what you want to do?” I begged my mother via text after a fraught conversation full of broken grammar and malapropisms.

“I just like to spend some time and enjoy dinner to celebrate your birthday with you,” she responded.

I paused for a long time. “OK. That is what I want.”

Five minutes later, I fled upstairs and muted my sobbing with a pillow. My 9 1/2-year-old son walked in on me heaving and ran to the stairs declaring to his three younger siblings, “There’s an emergency! Emergency! Come see Mommy crying!”

Just thinking of the exchange a week later, my chest seizes up and I choke down my panic to finish this sentence. In retrospect, it seems ridiculous and overblown. Why would a simple (albeit frustrating) text exchange devolve into desperate weeping?

Surely, it was just a combination of cultural and language barriers. But I know it is also pain, miscommunication, and fear that 41 years of a million interactions have deposited, choking us like fine silt.

The aftershocks of our parents’ sins reveal themselves in the most inopportune moments.

• • •

I am always astonished at how fragile we humans are. How easily we burst open, leaking everywhere.

Every time my children hurt each other, I ask them if they have the power to heal what they break. Do they have the ability to re-grow an arm or a leg on behalf of their sibling? Can their half-assed apology — or even their most sincere ones — help someone un-hear their mean words?

It is so easy to break things. So easy to destroy. So easy to ruin. All too often, what has been unmade cannot be made anew. It is irrevocably changed. Transmuted.

White evangelicals love to co-opt the Japanese art of kintsugi as some metaphor for redemption and healing since it is the process of repairing broken pottery by using gold dust mixed with lacquer to join the pieces back together. They justify our suffering, saying God makes something beautiful out of trash.

Forgive me if I’m uninspired; I’d rather not be shattered in the first place just to become art. I am content to be regular crockery.

Besides, what happens if our pieces are too small to be re-joined? What happens when we are reduced to rubble and dust? What happens when it is our parents who render us into nothing?

• • •

Eight years ago, right before my second child was born, I chose to cut myself and my children off from my abusive father. He has never met my three youngest children. My husband’s father died three days before my oldest child was born. My kids will never have a grandfather in their lives.

I still grieve.

I occasionally wonder if excising my father from our lives is the Christian thing to do; if Christ would give up on him as I did. I find that I do not care. I am no Messiah, carrying the world’s transgressions on my body. I bear enough wounds from my father; I refuse to subject my children to more.

In moments of cold clarity, I consider cleaving from my father my greatest act of love. I was shielding my children from him. (Little did I know that I would turn into a monster from whom they needed protection.)

My second greatest act of love was returning to therapy for the third time in my life and persisting.

• • •

When I used to tell my story, I cast my father as the villain. He was the charismatic lead of my young life who betrayed us wholly, actively tearing apart our family with his own hands. My mother, brother, and I were the passive victims; only my father had agency with his adultery, lies, and physical abuse.

I repeated this narrative so often, I never questioned it. Anytime my husband or my therapist hinted at my mother bearing some responsibility, I exploded. I shut down all discussion and balked at their insinuations; I refused to discuss even why I found it so upsetting.

Except it wouldn’t go away.

My fury, stewing in my subconscious, tainted my interactions with my mother, who I love. I dreaded conversations with her. I hid when she came to pick up my kids for their weekly outings. I was always busy. I limited our dealings to texts so that I could have time to formulate responses and scream at the screen.

I was furious that my mother — the one person who should have protected my brother and me — failed. She failed spectacularly.

Of course, as an adult, I realize she was so young and frightened. She had no idea what she was doing. I’m sure she felt trapped by the patriarchy of our Taiwanese background and our Chinese church. What lies did they spew to her — lies our communities use to keep women in their place — to shame us when we are not the ones who need be ashamed? Did they tell her it was her fault her husband strayed? Did they deceive her into believing divorce was a worse outcome than her and our safety? Did they demand she submit to him so he could be saved? To whom could she run?

But such logic has no effect on the child I used to be.

Well, that’s not entirely true. Such logic swaddled my anger and despair so tightly that I could not breathe. I could not even acknowledge my own feelings for fear that it would unravel the relationship with my only stable and remaining parent.

But my coping mechanisms were no longer working.

My children bore the brunt of my unmooring. I became my father: volatile, cruel, and vicious. I screamed at my kids in a constant, endless reminder that I was bigger and stronger. I destroyed their toys and possessions. I weaponized anything they loved — including myself. They were so small and loved me so much — almost as much as I loved them. And yet, I could not stop.

Even in our estrangement, I could not untether myself from who he was.

• • •

“Why do you always think I’m trying to hurt you? Why would I do that? I love you.”

At the time, I denied it because I didn’t know why I always reacted to my mother as if she were attacking me. Exploring my reasons would have exposed how I felt about her failure to protect us.

Though I don’t remember what argument forced that sentence from my mother’s mouth, they are some of the most important things she has ever said to me. I don’t always believe it, but I choose to operate as if it is true.

Years of therapy and writing equipped me to break free from survival mode and become a parent who could love my children in ways I was not loved. I learned to pay attention to my body’s physical cues before I erupted. I sidestepped potential landmines by ensuring I was properly fed, hydrated, and rested.

I apologized to my children. A lot.

I dragged them to my weekly counseling sessions for years due to lack of childcare. (I had been too ashamed to ask my mother for help.) I explained to my kids why I was going, and they called my therapist the Angry Doctor. They also complained that I was still angry, so clearly, the doctor was not working.

I wrote.

Most unexpectedly, although I sought therapy regarding my father, I found the most healing through forgiving my mother. I did so in the most cowardly of manners. Two years ago, I wrote a piece about why I was angry with her, exposing my pain and bewilderment. For once, I did not hide my article from her on Facebook.

She read it and immediately called my brother to ask why I was angry with her. My mother spent hours writing an apology and explanation to us, begging us for forgiveness and understanding. She asked to have dinner with me, and although I did not want to go, I went.

We did not spontaneously burst into flames.

• • •

I wish I could say everything was healed after that dinner. The neat completeness of presenting a metaphoric kintsugi bowl to everyone as evidence of Jesus’s work and forgiveness is tempting. It is good storytelling — but also untrue.

That is not how forgiveness works — at least, in my life.

Confronting my mother’s complicity in my abusive childhood was so difficult because I had to smash the narrative I told myself to make sense of my life. If my mother wasn’t perfectly good, then perhaps my father was not perfectly bad. And if he wasn’t uniformly terrible, perhaps I was wrong in cutting him from my life.

Except my mother admitted fault and has proven herself trustworthy as she has pursued her own healing and relationship with me and my children. My father has never said he was sorry. He has never taken any responsibility for his actions and refuses to do so even now.

I now see that he is human. I also know he is a human who isn’t trustworthy. He is not safe. I would always be afraid for my children’s physical and emotional safety around him, because they are not equipped for the life I had of constant hiding; they are too open and free.

Just as I have chosen to believe my mother means me no harm, I continue to choose separation from my father. I do not even know if I will forgive him in the future — and whether it is important that I do. All I know is this: he will never have the chance to break my children into possible art. They are priceless already.

Virginia Duan is a writer incapable of writing in brief. She swears. A lot. She finds it impossible to refrain from commenting online for the sole purpose of making people admit they are idiots. Fatal flaw is fatal. She discusses the deeply uncomfortable and humiliating with biting humor and glimpses of grace; loves the injudicious use of ALLCAPS; is #teamoxfordcomma; and always stans BTS. Virginia was a Listen to Your Mother SF 2016 cast member and you can find her work on various sites like Romper, Mom.com, and Mochi Magazine. She chronicles her mishaps at mandarinmama.com.

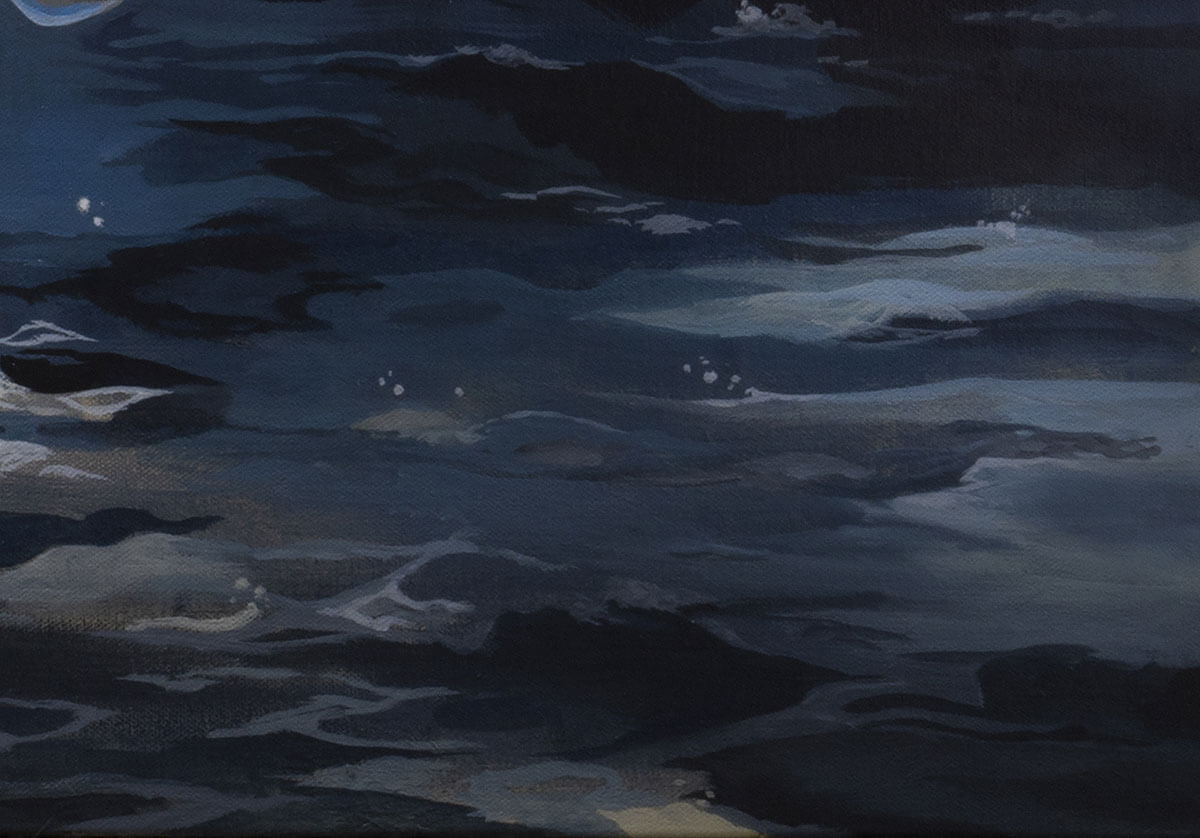

John Enger Cheng serves as creative director of Inheritance. He is a Los Angeles-based artist, designer and illustrator. He graduated from the University of Southern California Roski School of Fine Arts and is co-founder of Winnow+Glean. You can see his illustrative work and store at madebyenger.com.