At a White House briefing, President Joe Biden, when asked about the parallels between the military withdrawals from Vietnam and Afghanistan, stated that there was, “None whatsoever. Zero.” Vietnamese veterans and the Hmong military officers would beg to differ. The video showing hundreds of Afghan men surrounding a military aircraft, desperate to leave as the U.S. withdrew their troops in August, brought back memories for them. They too had been like the men pleading and grasping onto the tires of the aircraft as it took off.

While I’ll personally never know this feeling of utter desperation, my mother and father, their families, and their friends have felt this before. In 1961, the CIA recruited the Hmong people as covert operatives to fight against the spread of communism. By 1963, there were 19,000 trained Hmong operatives. By 1969, there were about 40,000. The number of recruits increased as the Vietnam War continued. In 1973, a cease-fire and peace treaty was signed. U.S. military forces were then required to leave. In 1975, South Vietnam fell to the Northern Vietnamese communist forces. With the North Vietnamese now in power, the Hmong were left in a most vulnerable position.

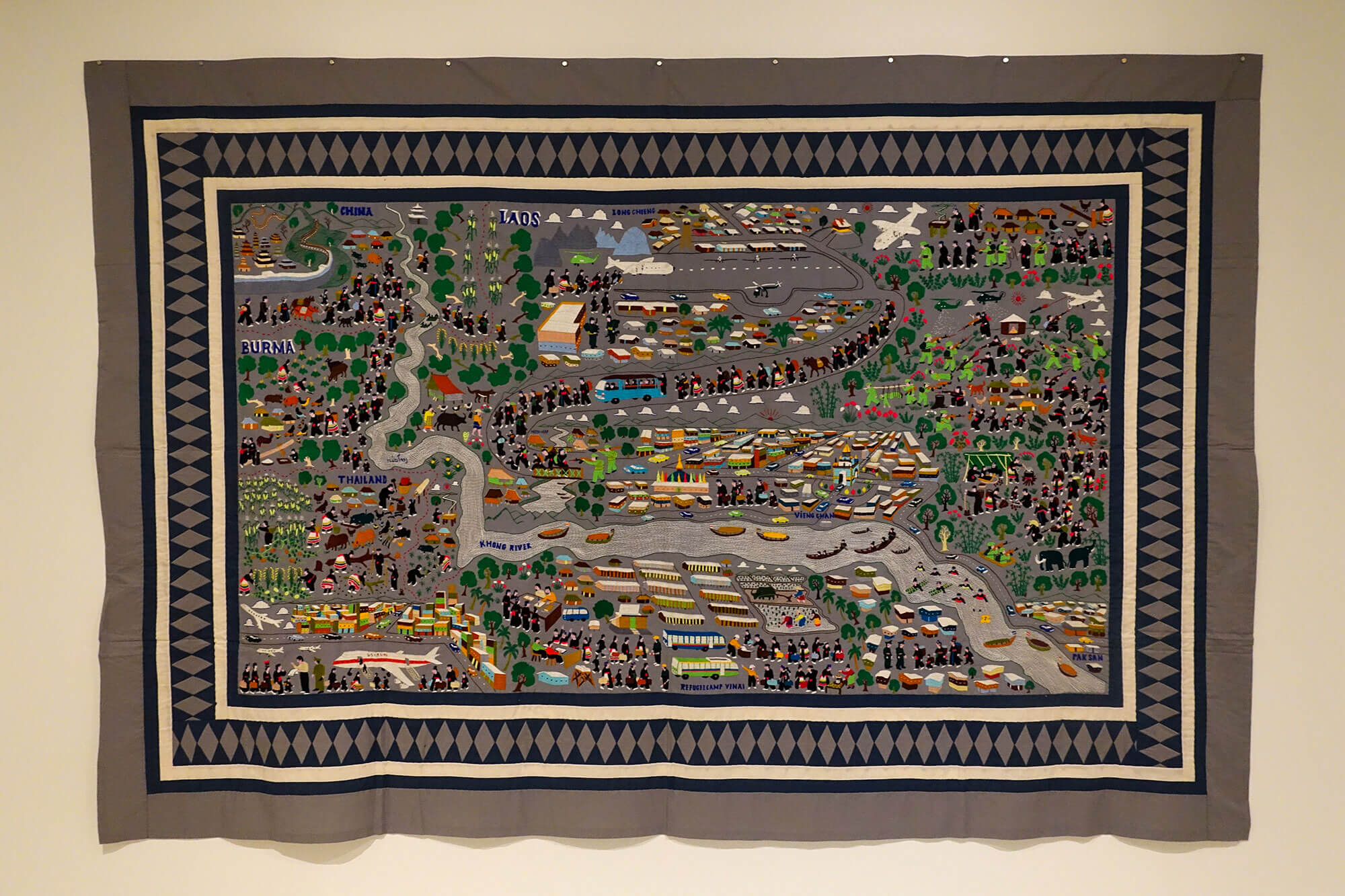

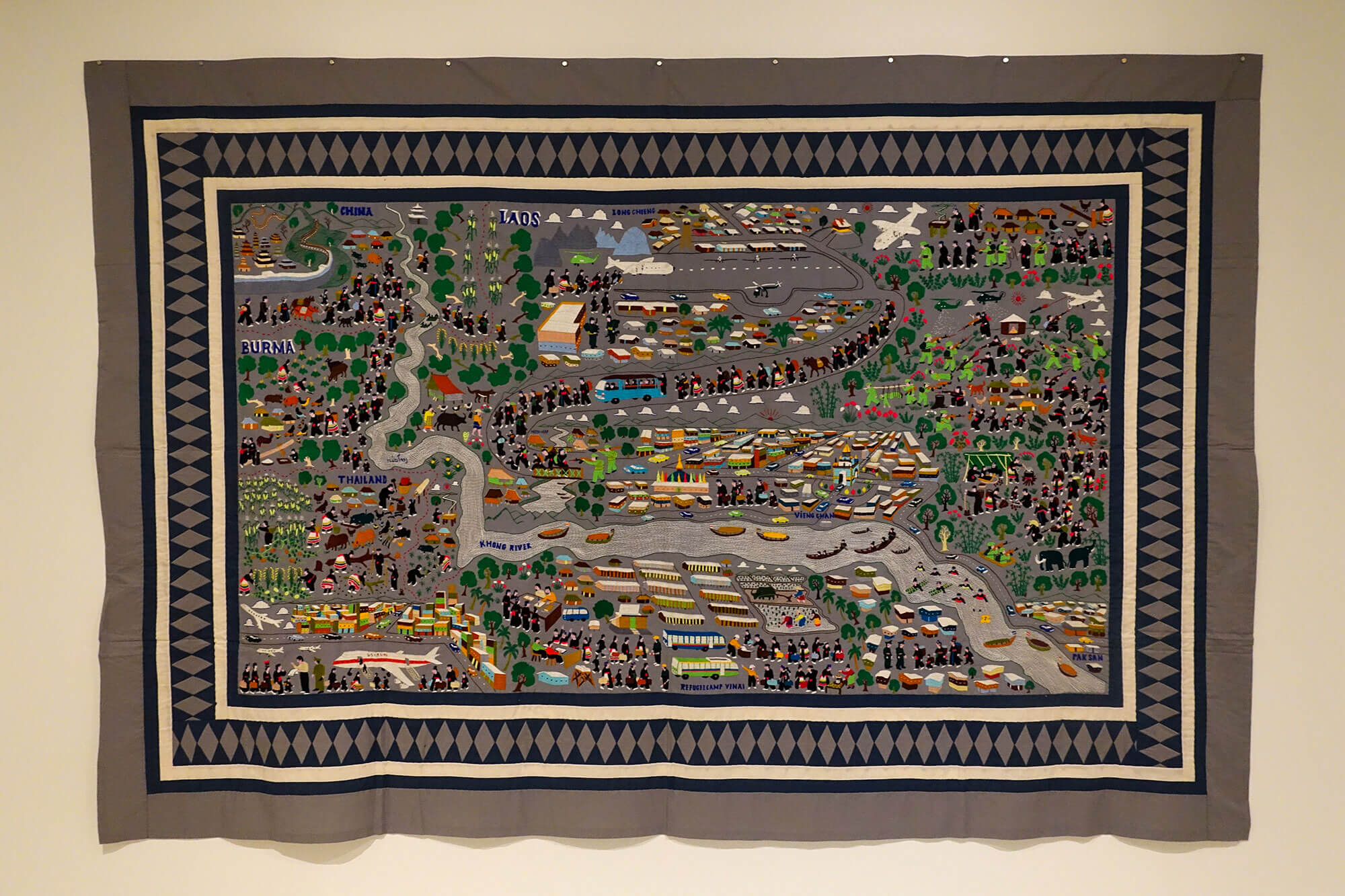

Like the Afghan families seeking evacuation at U.S. air bases, the Hmong too, swarmed the U.S. air base stationed in Long Chieng — a military base turned small town. Though some were able to leave, a majority of the Hmong people were left behind. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, about 2,500 Hmong allies were evacuated over four days in May of 1975. From the same source, about 120,000 Afghans — including 20,000 of those considered at-risk — were evacuated this past August. Those who were left behind had to find other ways to flee from the encroaching forces.

Though the experiences vary, I’ve heard over and over again the stories of families being hunted down by the Northern Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces; of family members drowning as they crossed the Mekong River to reach Thailand; of families hiding in caves and deep within the jungle; of families selling off valuable possessions for passage; of families using opiates to calm their toddlers in fear of being heard by their enemies; of families, full of desperation, making extremely difficult decisions.

My parents were barely teenagers when they had to leave their homes. My mother had lost her father to an illness during the Vietnam War. Due to patriarchy in Hmong culture, my mother’s family was looked upon with contempt for not having a male head of household. With no father, there was no value or honor given to the family. Her father had served with General Vang Pao — the main person of contact for the CIA — but that didn’t matter when the planes came to evacuate the military officers and their families. Without her father to vouch for them, they didn’t even bother to board the planes. My mother recalls an aunt telling her to stay because “Who would want to come kill you?”

Who do you turn to in times of crisis? What location is safe? Who is considered an ally? Fortunately for my mother, her older sister was at school when she overheard her classmates — who were children of the military class Hmong officers — talking about the war being over and the U.S. military leaving. With this newfound information, she devised a plan for the family to escape to Thailand.

My mother’s family consists of two brothers and four sisters. Her older sister, having already been to Thailand on previous endeavors, knew how to get there without getting caught by the patrols at points of entry. Unfortunately, the plan involved separating the family, because separation meant a higher chance of survival. Families traveling in large groups would be easily spotted, questioned, and turned back, or in the absolute worst cases, turned in to the enemy.

My mother’s sister separated the family into three groups: their mother and the two younger brothers; herself and her two baby sisters; my mother and her older sister. Each group had to have a convincing story in order to pass certain entry points. My mother doesn’t recall how they were able to get rides to Vientiane — a large city on the border of Laos and Thailand, but she does remember her fib. When they were stopped and questioned, she told them she and her sister were students on their way back to school grounds, which was believable enough to get them through and into Vientiane. Nobody knew when anyone would arrive at the designated meeting spot. My mother and her sister arrived first, followed by her older sister who devised the plan and her two younger sisters. They feared the worst when their mother didn’t arrive during the expected time frame. They waited, and their mother arrived days later with their brothers in tow.

Crossing the Mekong River was yet another hurdle. Though they stayed in Vientiane for about two weeks, they understood that time was limited there. A deal was eventually made with a Lao smuggler for $10,000 Laotian Kip. My mother recalls being skeptical about hiring this man. Desperate to leave however, they had no other options. At 2:00 a.m., during a rainstorm, all eight of them boarded this man’s boat with nothing but the clothes on their backs and a little package of belongings held tightly under their arms. After the crossing, the smuggler demanded an additional $10,000 Kip because he stated the boat shouldn’t have made it over with the number of people onboard. My aunt folded up the original $10,000 in half, counted $20,000 kip to the man, and told everyone to run.

My father’s family tried leaving on the military aircrafts in Long Chieng. My grandfather, who was a ranking officer in the military and was stationed away at a different location, told his family to try and leave on one of the planes. Like many others however, no matter how hard they pushed or clamored with the authorities, my father’s family wouldn’t be allowed on board.

My father doesn’t recall how or why Thailand was known to be the place of refuge, but it would become their next destination. Unlike my mother’s family, his traveled in a large group with my father’s cousin as the lead man in their operation. Having access to trucks, they made their way to Vientiane. Along the way, they were also met by patrols. When questioned, they told them they were on their way to the rice fields to gather the harvest.

Once they arrived in Vientiane, they paid a Laotian man to help them cross the Mekong River. After two weeks, they were fortunate enough to board a plane that took them to Nam Phong, where the infamous Ban Vinai camps were located. After staying there for nearly a year, my father’s family landed in Elmhurst, Illinois, in October 1976.

Similar stories have already been documented for Afghan men and women as they try to cross over into Pakistan and other neighboring countries. Many Afghan people left their homes for fear of Taliban retaliation. Some, like the Hmong, had to leave family members in hopes of meeting again somewhere. Their stories are still unfolding.

We are two very different people groups, but our lives have been deeply affected by the same powerful, overwhelming nation. That our stories are intertwined in this way should give us pause. What is this power, the power to disrupt and uproot families and also to claim to give hope by offering a new kind of future? The power to devastate and the power to create something anew?

The creation of something new comes along with its own distinct challenges. While a majority of Americans support the resettlement of Afghan refugees, it becomes an issue when the resettlement is in their own neighborhoods. The fear of the other is extremely powerful. Before and during Trump’s presidency, his messages often suggested immigrants were to blame for “stealing jobs” and placing an unwanted burden upon Americans. While the data proves otherwise, it’s obvious that there are clear biases against immigrants and refugees. The belief is that they’re going to disrupt and even dismantle the foundations of the communities they resettle in. Sentiment quickly shifts from responsibility to blame. Empathy is lost, and fear removes the capacity to see a fellow human being. For refugees navigating a new and foreign world, the effects of racism and classism compound and complicate their already complex lives.

And yet, despite these challenges, refugee communities continue to create anew. Hopeful determination is the toolset for refugee families. In the years since the Vietnam War, the Hmong have become business owners, politicians, doctors, journalists, and just recently, an Olympic gold medalist. Though the success stories are praiseworthy, it shouldn’t mask the hardships frequently faced by immigrant and refugee families. Hmong people have less access and more barriers to economic sustainability, education, and various other social determinants when compared to other Asian American groups and to the U.S. population as a whole.(1) Though there is still much work to be done, the strong familial culture of the Hmong empower and offer hope of a future yet to be determined. I suppose that’s all part of creating something new.

That Vietnamese and Hmong Americans see themselves in the Afghans resettling in the U.S. is not surprising. From experiencing the atrocities of war to learning English, and everything in between, we can articulate some of the feelings that Afghan refugees may be experiencing. It is precisely this reason why we have a responsibility to the Afghan refugees. As we remember our own stories, we must listen intently to theirs. This responsibility is different from that of the U.S. government. The government owes it to the Afghan refugees to keep their promises to help them as allies. Our responsibility, through active remembrance, is to advocate for the Afghans so that, perhaps, we can create better conditions for them through policies and law, and by holding the government accountable for creating such circumstances.

It’s conveniently easy to forget these stories. If there’s a lesson to be told here, we must continue to tell our stories again and again, lest we imagine that there are no parallels whatsoever to current crises. History repeats itself otherwise.