An inside look at the way COVID-19 has changed hospital chaplaincy, through the eyes of two Asian American chaplains in New York and California.

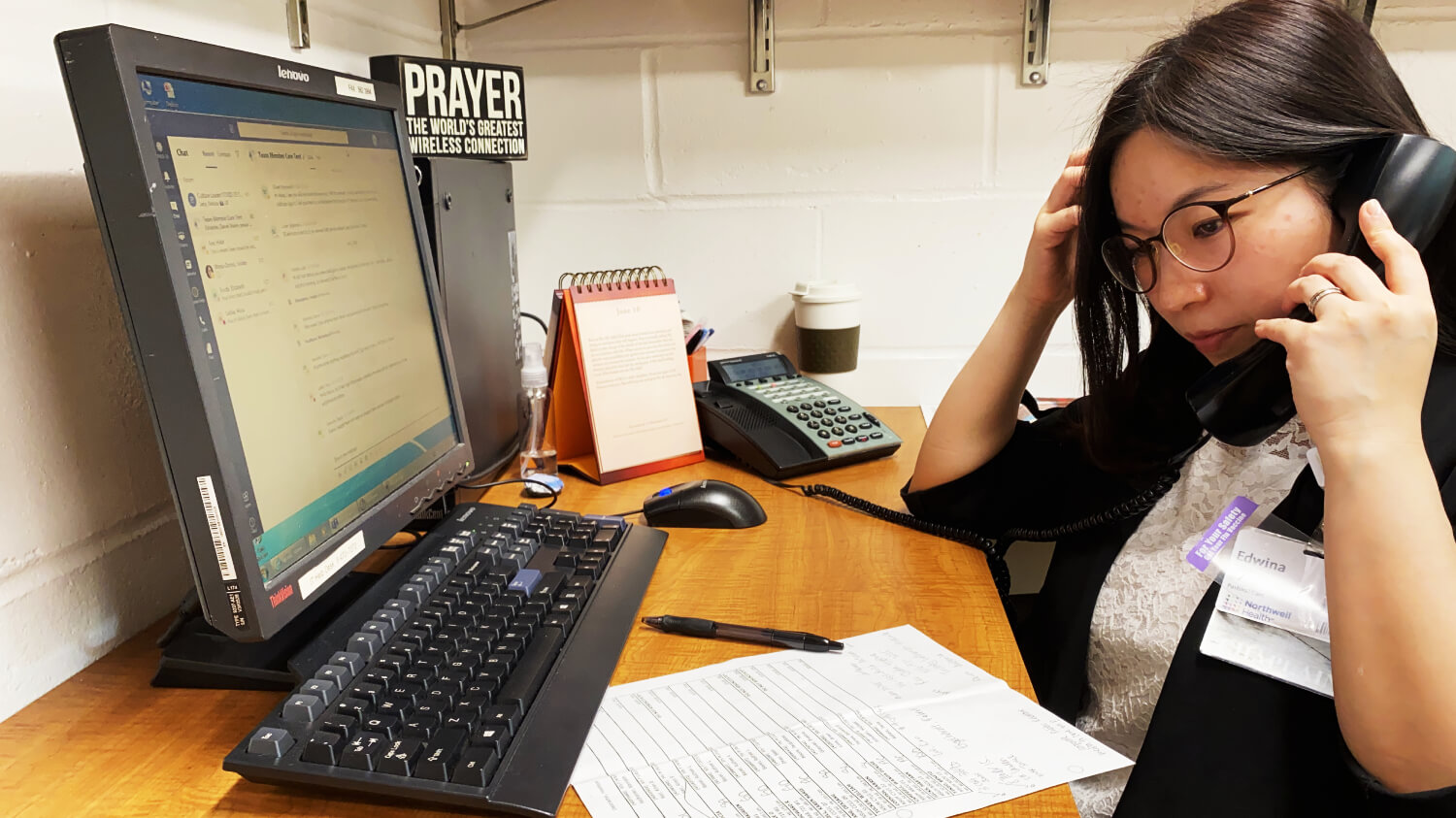

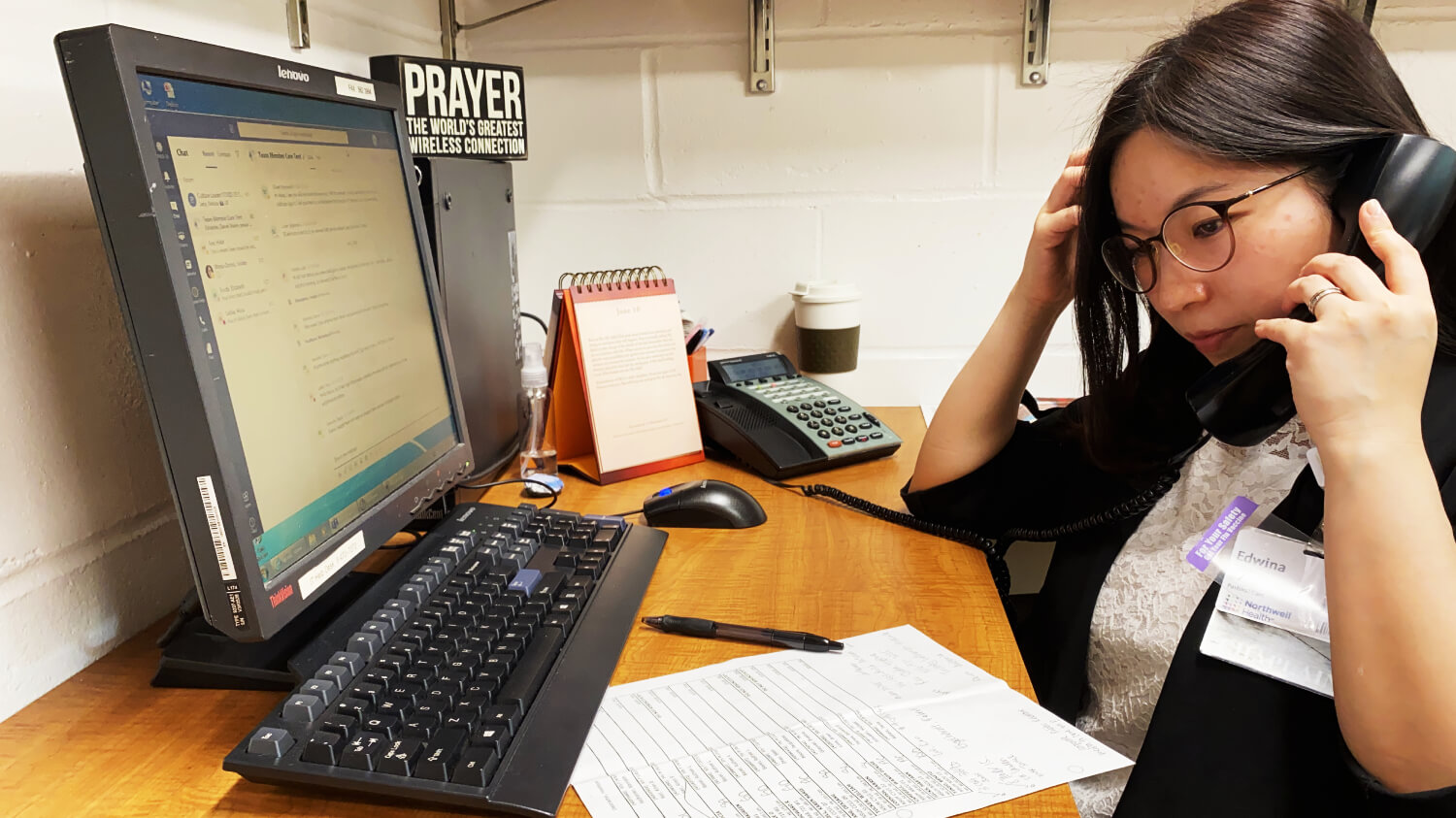

In a once bustling lobby, only a few staff were in sight when Edwina Chan entered North Shore University Hospital, located just outside of New York City, on April 2 — the first time she stepped foot into her hospital since the coronavirus outbreak. Fully aware that she was risking her life by walking into a coronavirus petri dish, Chan had geared up with an N-95 mask, praying that she wouldn’t catch the malignant virus, or worse yet, bring it home to her husband.

As she made her way to the cardiac short stay unit, the station she was now assigned to, Chan came upon thick, antimicrobial curtains that had been erected to seal off the entryway and prevent contamination. The CSSU had been converted into a COVID-19 unit almost overnight due to the overwhelming number of infected patients, just like its many other floors at the hospital, save for a handful of units. Fear enveloped her heart as she pulled down the zipper to enter, bracing herself for what she might see.

As soon as she stepped in, a nearby nurse immediately recognized that she was new to the floor. “Where are you coming from? Why are you coming in?” she asked. “You shouldn’t be here.”

“I’m a chaplain,” Chan replied, recognizing the nurse’s instinct to protect visitors from unnecessary exposure. “I’m here to provide support and I just want to do the blessings of the hands for the staff, whoever wants it.”

Walking down further towards the nurse’s station, Chan could see bed after bed with patients hooked up to ventilators.

In late March and April, New York hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients. After the state reported its first death on March 14, the number of cases and deaths spiked quickly. At the peak in mid-April, 800 people died in one day and 2,000 to 3,000 new patients were being hospitalized daily. Doctors described the hospitals like war rooms, with the staff battling the invisible virus, scared for their lives as patients fell around them, victim to the enemy. All around New York, hospitals had converted floor after floor into COVID-19 units. Thankfully, as of June 10, there were only 79 new hospitalizations across the state. The worst is almost over, though the disease has exacted a virulent blow on New York, taking more than 24,000 lives. Chan deeply feels the strain that healthcare workers are in and decided to put her own life at risk to provide spiritual and emotional support to these front-line workers.

Ministering to Health Care Workers

About 10 nurses and staff created a huddle around Chan, eager to receive prayer. Some shared about how they worried about their families. Others shared about how lonely they felt, because they had chosen to sleep in a nearby hotel to prevent bringing the virus home. Others worried about contracting the disease themselves. Another was afraid of the unknown duration of the pandemic. Another asked for prayer for her friend, who contracted the disease. Chan noticed that many were tense, exhausted, and anxious. She acknowledged their feelings and emphasized that she was there to support them.

“The whole medical staff, me, everyone is feeling powerless,” Chan explained. “It’s really tough handling that.”

Prior to the pandemic, Chan spent almost all of her time ministering to patients at their bedside. Now, she is constantly offering to pray for the staff and checking in on their well-being.

“We can’t hold hands, but let’s stretch out our hands, palms up, and receive,” Chan said to the group. “Because we have to give and give and give, but we have to receive from the Almighty God, from the Creator.”

She proceeded to say a prayer, ending it with blessings of hands.

“May the work of these hands bring healing to all the people that you touch. May the God who formed these hands guide them to bring the healing touch of life. Creator and Sustainer of life, bless these hands to be instruments of healing. Blessings and appreciation to the many tasks these hands and all these people can do. Amen.”

Ministering to Patients

As a chaplain, being able to offer the gift of presence to the sick and dying — sitting alongside them and offering a listening ear through their moment of deepest fear or greatest uncertainty — is a ministry that Chan cherishes deeply. Now during the pandemic, Chan is not allowed to enter coronavirus patients’ rooms. Where a reassuring hand clasp or the warmth of a hug used to be the language Chan bestowed as a gift of presence, she now must rely solely on her words to give comfort to the dying and families mourning, separated from them by the screen of her iPad or phone.

Interactions between patients and loved ones are also conducted virtually or through phone calls now. To prevent the spread of the virus, New York hospitals have barred all visitors from stepping foot inside the building, save for extenuating circumstances such as when the patient is at the end of their life or if a woman is in labor, though these visits are also limited. Hospitals across the country have implemented similar policies.

Due to these restrictions, COVID-19 patients are dying alone. They may die before their family members have had a chance to phone in or visit them. Families are no longer permitted to stay inside the room to watch over them or stay overnight with them, being physically present as they transition out of this life. It’s a phenomenon that has crossed Chan’s mind many times — as a young girl, her own mother was frequently hospitalized, and Chan feared that she might suddenly pass away without Chan being by her side.

“For me, the hardest part is I can’t be physically present with the ones suffering, whether they are patients or family members of a patient,” Chan explained. “I can only do FaceTime or call, and that’s different from being there with them, holding their hands.”

One interaction with a patient’s daughter has stayed with Chan. One morning in late April, while talking with Chan over the phone, she shared a profound request:

“Can you hold his hand for me?”

Knowing that the daughter could not be by his side, Chan felt moved to do everything in her power to fulfill her request. Although Chan had all the proper protective gear to go inside, she unfortunately was not allowed to go into the room. She decided that she would set up a video call with the daughter and her father the next time the nurse could go into the room with an iPad. Chan broke for lunch, wanting to be fully replenished before she offered them spiritual care. However, once Chan returned, the nurse manager informed her that the father had already passed away, news that came as a shock — neither Chan, the daughter, nor the staff had suspected his death to be so imminent. Though he was placed on a ventilator to facilitate his breathing, he had not been referred to Chan as “actively dying,” a term the staff use when the patient’s death is expected in less than 24 hours. A physician called the daughter to deliver the heartbreaking news.

After Chan collected herself, she later called the daughter. They both broke down in tears. Chan listened, sharing in the grief and the shock. At one point as the daughter vented her bereavement, she said, “There’s no more suffering for him now. It’s all OK.” She shared that she had video called him two days prior, when he was more alert. Chan graciously affirmed her belief that her father was now in a better place, resting in eternal peace with the Lord. Despite the inability to be present in her father’s death, God was still with him even as he took his last breath.

“This is suffering, this is regret, this is what happens in life.” Chan shared. “But as long as we have each other, as long as we have God together, it’s going to be OK.”

“After all, death is the thing that one has to go through alone with God. Nobody can really be there. I’ve learned that presence in the Lord and presence with others in the Lord may not be physical, but spiritual. I have less fear of not being there but [am] trusting God is there for any death.”

Caregiver Trauma

Post-traumatic stress is something that is felt by health care workers across the board, including Rev. Joseph Choi, a senior chaplain at St. Jude Medical Center in Fullerton, CA. Though the hospital only treats around 15 coronavirus patients a day, St. Jude has restricted visitors and turned their sepsis unit into a COVID-19 unit. Choi, who had previously been assigned to the sepsis unit, was suddenly ministering to coronavirus patients day in and day out.

“Just doing a self-checkup, I probably have some of the symptoms like nightmares,” Choi explained as he looked away and breathed in deeply. “Feelings of helplessness and extreme sadness, recurring memories of a particular patient or family member.”

“Anyone who is in this field will eventually end up with minor or major caregiver trauma. I would probably qualify for a lot of those symptoms.”

PTSD is often linked to people who have served in the military, but as one psychologist explains, “PTSD is a well-established consequence for health care workers who worked through deadly pandemics.” Hospital workers, who are constantly being exposed to the virus and are witnessing increasing amounts of death, have had to put grieving on the backburner while they dutifully press on. Once the adrenaline dies down, they will be forced to confront the lingering psychological effects of the pandemic.

Reaching out to others for support is vital in the healing process. In the beginning, Chan shut down in response to the deluge of devastation around her. “Pray that I can cope healthily and can really process before God,” Chan wrote to a friend in April. “I feel like I can’t quiet down, and I also feel like running away. I know I can’t offer myself fully when I’m so overwhelmed.”

After processing her emotions with her friend, Chan began taking daily walks to pray and unload her thoughts and feelings to God before starting her day at the hospital.

“God is the counselor who untangles my thoughts and accepts my emotions and my whole being,” Chan said. “God is present with me, and that really helps me to be present with others.”

Serving Diverse Populations

In addition to ministering to patients and staff, Choi is also a certified Korean translator. In a region with a sizable Korean population, that skill has become invaluable in helping Korean immigrant patients and their families who do not know how to navigate complicated medical concerns in a time of mounting distress.

In one instance, Choi was called to visit an actively dying Korean patient. The wife and their young son were allowed to visit him before he was taken off the ventilator, but due to their limited English, they could not communicate with the nurses. Choi stepped in to translate, explaining the procedures for seeing their loved one and how to properly dispose of their personal protective equipment. Right before the wife and son went in, Choi gathered them outside the window while he spoke Psalm 23 and the Lord’s Prayer in Korean over them. After they came out, Choi had a brief moment to speak with them.

The family was not able to actively attend church, nor did they have a pastor.

“A lot of those in the immigrant communities who don’t speak English well are not able to go to church because of the type of work they do,” Choi said. “Which is quite unfortunate.” These immigrants often work during the weekends and at odd hours in various places, including restaurants, import/export companies, and clothing manufacturers.

For that short time, Choi took on a pastoral role and offered whatever care he could give them. In fact, the Korean language lends itself to allowing people to view chaplains more like pastors because there is no word for “chaplain.” Whenever he encounters Korean patients and their family members, he introduces himself as a pastor and finds himself naturally fitting into the shepherding role of a minister.

“Taking on that pastor role might not be for everybody,” Choi said. “But in the Korean community, because there is such a strong tie to the Korean immigrants and to the church, that type of role-taking does seem to work.”

Among Korean immigrant patients, Choi has observed a power dynamic at play between the less-educated immigrant and the skilled doctor, where the immigrant patient — particularly an elderly one — will take what the doctor says at face value, even though they might have lingering questions or concerns. Though doctors can have a call-in translator service, it’s not as effective as having an in-person translator. So when Choi shows up, he often acts as a translator of language as well as a translator of their hearts, helping them parse through their medical questions with the doctor while also reading and tending to their spiritual needs.

“The fact that I can speak their language adds to the fact that I am able to help those who are vulnerable,” Choi explained. “When scripture talks about the widows and orphans and taking care of them — sociologically speaking, those [immigrants] are the most vulnerable. They don’t have any safety nets.”

•••

For Choi and Chan, what motivates them to press on is their desire to fulfill Jesus’ commandment to love others as they would love themselves.

“I don’t think I can show my love for God just by spending eight hours a day reading the word and then praying another eight hours,” Choi said. “It says in the book of James, you show me your faith by words, I will show you my faith by action. If the hospital needs me, then it tells me there is a responsibility for me to continue doing what I do.”

“Every single breath is a sign that the Lord sustains my life,” Chan said. “It’s a sign that He wants me to keep going and doing what I am doing.”

“The coronavirus has made a profound impact on me,” Chan continued. “In 2 Corinthians, it says when I am weak, then He is strong. I feel blessed to know my weaknesses and humanity’s weaknesses because when we know that, then we seek the grace of God. Overall, this pandemic has helped me to trust God more and see His loving compassion in ways that I have never thought of.”

“Never have we experienced that the whole world is having the same experience,” Chan said. “If suffering is happening to the whole world, then grace is also for the whole world.”

Joyce Chu is a storyteller who loves to illuminate humanity's experiences and connect the world to them through various forms of art. Hailing from sunny California, she learned all there is to know living in the magnificent concrete jungle of New York City. You can see more of her work at journartist.com, and follow her on IG/Twitter @joyce_speaks.