“There can be no justice without memory–without remembering the horrible crimes committed against humanity and the great human struggles for justice.” - James H. Cone

Across the ocean on a small island; on the shelf of a small seminary library, I came across the book "Black Theology & Black Power" (I still believe the ghosts of my ancestors guided my path that day). I read the preface with the intent of just skimming and going on to the next, more common theological literature used in the Pacific, such as Barth, Tillich or Process theologians like John Cobb. In contrast, I had almost finished reading the entire book when the librarian turned the lights out to close. I rushed downstairs and begged her to let me check it out to finish reading it later that evening.

Something happened that day. In essence, James Cone’s theology preached to a corner of my consciousness that had thus far been unexploited. My faith was profoundly impacted in a way that was truthful and sincere. It was primarily his use of the black experience in America that rattled my theological senses. To paraphrase Paulo Freire, who wrote the foreword for the 1986 edition of "Black Liberation Theology", Cone’s work is a stimulus for one’s own struggles, especially those with histories of oppression who have been conditioned to view God and therefore the Gospel through an imperial lens. Cone’s argument that any interpretation of God that ignores black oppression cannot be Christian theology became a catalyst for how I could/should critically engage the doctrines, creeds, and imperial culture of European Christianity in the Pacific.

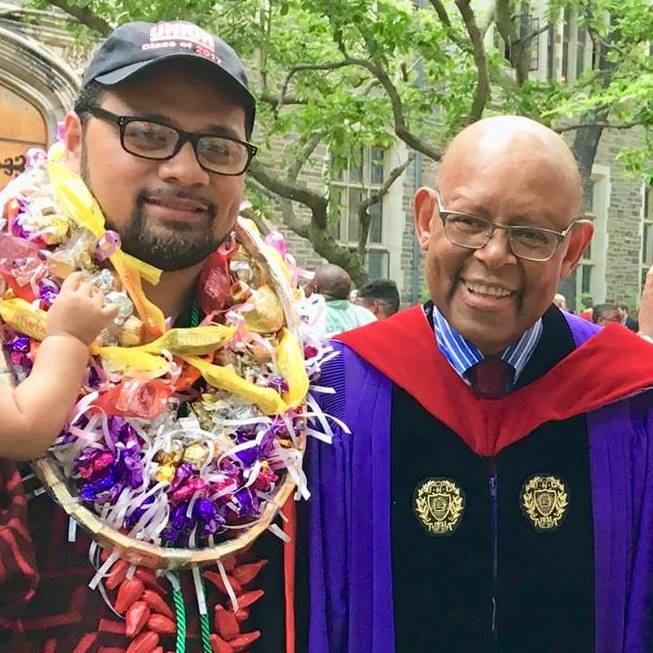

After reading Cone’s seminal text and consulting with my mentor in Samoa, Dr. Ama’amalele Tofaeono, I did some research to find out where this “disturber of the peace” was. To my amazement, he was still teaching. Cone was at Union Theological Seminary in the city of New York, and I immediately knew that was where I had to pursue graduate studies after seminary in Samoa. I applied, got accepted, and journeyed with my family — my wife who was eight months pregnant and our two toddler girls — across the vast Moana (Pacific Ocean) to the eastern coast of the U.S. Cone’s black liberation theology was a spiritual calling that stimulated a deeper longing to know God through the lens of the oppressed. In other words, Cone’s ontological black Jesus brought me closer to a Christian faith that acknowledged the colonial past and pain of my ancestors, and I was determined to not let that history have the last say.

Dr. Cone was my M.A. advisor at Union. Admittedly, I was filled with a sense of idealism typical of first year students who enter seminary ready to change the world. I took his courses on Systematic Theology, James Baldwin, and God, Suffering, and the Human Condition. Echoing the remarks of Rev. Dr. Raphael Warnock (Cone’s former Ph.D. student at Union) who delivered Cone’s eulogy: “Bar none, professor James Cone is the best classroom teacher I ever had.” There was no elite intellectual divide in Cone’s classes. He taught and learned, critiqued and received criticism, and challenged his students to “find your theological voice”. I briefly discussed Ph.D. aspirations with Dr. Cone during our monthly meetings, mainly because I was passionate about the struggle for liberation of Pacific people. However, I would soon find out that it took more than passion to write. I lacked the discipline and intellectual rigor that the suffering of my people deserved. Dr. Cone made this clear to me when I wrote a reflection on my people’s suffering and the need for a more relevant theological discourse. To say the least, I was devastated by his comments on my reflection:

"The suffering of one’s people deserve the most thoughtful and well written reflection we can offer. And I do not think this reflection is your best, even though it is very good as a beginning theological reflection. If this is your best, then you need to give serious thought if the doctorate in theology is your vocation. I have no doubt that you have the intellectual ability to do it but you need to be called to develop the discipline to do it ..."

Dr. Cone checked any idealism I had prior to attending Union, as well as all measure of confidence that my writing skills at the time were sufficient to pursue doctoral work. Still, in our following meetings, he continued to critically and constructively build my confidence. He never let me slide with mediocre thoughts and constantly held me accountable to my ancestors and the people of the Pacific. Eventually, he encouraged me to pursue doctoral work, but only if I were committed to cultivating the discipline needed that could help me best articulate my love for the people of the Pacific and their quest for true liberation through the life ministry of Jesus.

In his 1999 text, "Risks of Faith", Cone stated:

“There can be no racial healing without dialogue, without ending the white silence on racism. There can be no reconciliation without honest and frank conversation. White supremacy is still with us in the academy, in the churches, and in every segment of the society because we would rather push this problem under the rug than find a way to deal with its past and present manifestations.”

As I reflect on Dr. Cone’s legacy and the impact of his black theology of liberation, I can narrate today what began years ago in that small seminary library in Samoa. It was, in more ways than one, my conversion from Christian conformist to Samoan liberation theologian. Dr. Cone’s texts and teaching facilitated a deeper understanding of my context and the manifestations of European ideology in Samoan religion and society. It became clearer to me that the tentacles of white supremacy through colonial missions still laid claim to the physical, mental and spiritual lives of Pacific people.

In Samoa, the indigenous rituals and beliefs of our ancestors are still considered “lewd” and “wicked” practices by both white settlers and Samoan “fia palagi’s” (the equivalent of an “uncle Tom”). The islands are now physically and psychologically divided as a result of colonialism between Independent Samoa (once a European colony) and American Samoa (still a U.S. colony). The missionary god still regulates the spiritual ethos of the islands as Christian discipline, creeds and doctrines, and European liturgical orders are held in esteem as consecrated right worship over indigenous practices that sustained the once sacred balance between human beings and nature.

As a result of colonial ideology and their introduction of racial caste, Samoan people are now conditioned to view their own light complexioned people as civil and first-class while the darker complexioned are stigmatized as uneducated or lower caste. Images of a blond, blue-eyed white Jesus on stain glassed windows adorn cathedral-like churches of the islands, imprinting generations of Samoan children with the image of a white Jesus, and a white theology to match. European missionary monuments are ubiquitous island-wide, while heroes and freedom fighters of old Samoa are confined to memory — memories that fade with each passing generation.

In a broader sense, Cone’s theological lens of the lived experience and the life ministry of Jesus exposes how the poor and helpless communities of the Pacific are manipulated and divided through miseducation and false religion. I wrestle with the contradictions in the way resources are being exploited for profit while the church, white and Pacific churches, are silent.

As I think of Dr. Cone’s painful retracing of slavery in America and the lynching of blacks during the era of Jim Crow laws and segregation, I’m reminded of West Papua New Guinea, which continues to endure a “silent genocide” of both people and culture through the occupation of their lands by the government of Indonesia, who are the protectors of U.S.-backed corporations that exploit natural resources in the region at all costs. I think of islands like Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Solomon Islands, which are existentially threatened by rising sea levels as their cultures and lives are viewed expendable by corporations and governments that profit from human induced changes to the earth’s climate.

Had I not come across Dr. Cone’s work, it may very well be that I would have conformed to missionary teachings that instructed Pacific people to remain still, obey and be concerned only with justice that does not disrupt the status quo, which translates to white missionary authority. Of course, that was not the case, and Cone helped me to interrogate my God-talk. I asked myself constantly: Who is this god that does not speak to the suffering of my people, their history and culture? What does the god of missionaries say to the people of West Papua, the loss of their culture, and the displacement from their lands? How do I justify upholding and perpetuating theologies of dominion and ownership of creation while rising seas threaten islands like Tuvalu and Kiribati?

Dr. Cone helped me see clearly who Jesus was, and was not. The missionary god was not God, and was totally detached from the story of Jesus in the Gospel. Nowhere was Jesus silent and for the oppressor. Nowhere was Jesus a friend of empires and religious elites. Nowhere was Jesus disingenuous to the plight of the poor and downtrodden. And nowhere was Jesus a white supremacist who exploited the earth, erased cultural memory and murdered indigenous people. Something happened that day in the library. It was the beginning of the slow demise and eventual death of the god of colonialism and domination, and the emergence of the God of justice, love, and liberation. As Dr. Cone would always say, “Theology is a language of imagination. God is always found where we don’t expect i.e. the manger, cross, or lynching tree.” I found God in the rituals and indigenous practices of my ancestors, and Jesus was not indifferent to their cultural expressions and ways of knowing. White supremacy, racism, classism, homophobia, and evil continues to flourish because the genuine Word of God through the prophetic witness of prophets like Dr. Cone remains a mere footnote in our God-talk.

It has been two weeks since Dr. James Cone went to be with the ancestors on April 28, 2018. I loved that man as a mentor, teacher, friend, Christian and prophet of the Gospel. As many have testified elsewhere, Dr. Cone was never one to command disciples or followers. He wanted his theology to be a pathway for not only African American students to articulate their history and suffering, but all people, i.e. Asian, Latin American, African, White American/European and Pacific Islander, who were on the side of the poor and oppressed to find their theological voices in the process of exploring black liberation theology. The world is still processing the absence of his physical presence. But he left a rich legacy behind for generations to come.

In the Pacific, theology must be on the side of the poor and oppressed for it to be Christian theology. In fact, Christian theologians and pastors need to return to the teachings of the ancestors to fully embrace the Gospel of Jesus and the message of the Cross. To understand the sacrifice of Christ, we must understand our own colonial wounds and how the message of Christ meets us in and through our indigenous ways of knowing. Bearing the Cross of Jesus in the Pacific means devoting one’s life energy to annihilating oppression and the spread of white supremacy and all its vices. It is not the way of cowards and conformists; rather, it mirrors the conviction of Jesus and is willing and ready to take risks for the sake of truth, love, and justice. James Cone did to my mind what I believe God intended all along: to use my mind for the sake of the other, the oppressed and suffering of the world. Or in Cone’s own words, “theology is loving God with your mind”.

Today, I love God more with my mind, body, and soul because of Dr. Cone’s words and the humanity he showed me because he cared about the suffering of my people as much as he did his own. I must say I miss him dearly. But Dr. Cone remains with us insofar as we continue where he left off. That is, with essential Jesus humanity, the liberation of the poor and oppressed, and a Christ-like conviction for love of one’s people and the recognition of their full humanity as God intended.

Rest well, teacher. I, and the people of the Pacific, will move forward in love and justice. I have found my Voice!

Pausa Kaio (PK) Thompson is a Samoan American clergy, activist and theologian. He is an alum of the Kanana Fou Theological Seminary in American Samoa, Union Theological Seminary in the city of New York, Boston University School of Theology, and is a Ph.D. student at Claremont School of Theology. His scholarly work accentuates the theological discourse, indigenous culture and wisdom, and social justice issues of Samoa, and Samoans in diaspora. His ministry encourages people to be change agents in the world by invoking a more socially conscious ethic of Christian practice.