To the man who murdered my brother,

I don’t expect you to read this right away. In fact, I would suggest that you wait and allow this letter to sit idle for several years until you are ready to hear what I have to say. I should clarify; I don’t harbor ill intent toward you, nor do I desire vengeance or retaliation. My intention in writing this letter is healing — plain and simple. Nevertheless, I anticipate that this letter will undoubtedly elicit feelings of deep guilt and immobilizing shame. If, at this point, you find yourself emotionally compromised and unable to continue, please stop.

Hear me when I say that this isn’t about punishing you. I’m not interested in hurting you or inflicting pain, but engaging the content of this letter requires a preliminary journey of humility, honesty, and self-reflection. Knowing this, if you feel you have journeyed deep within, if you have found the courage to confront that inner darkness, and if you’re prepared to receive what I have to offer, then please, continue on.

I want to tell you my brother’s story.

On the night of Alan’s murder, you held his life in your hands. Although you could have never known the value of what you were holding when you pulled that trigger, I did. And as difficult as it may seem, I think it’s important for you to know what that value was.

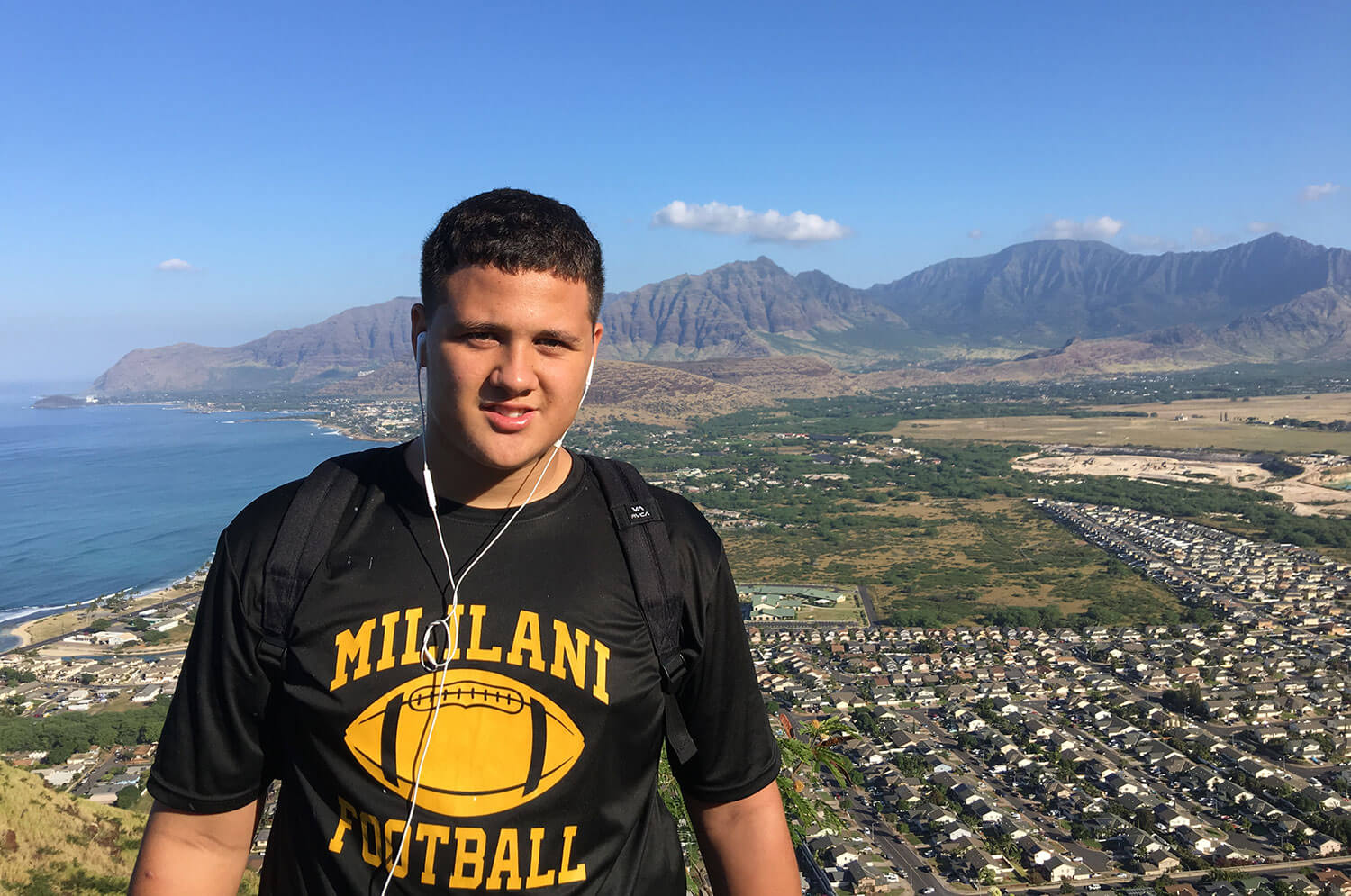

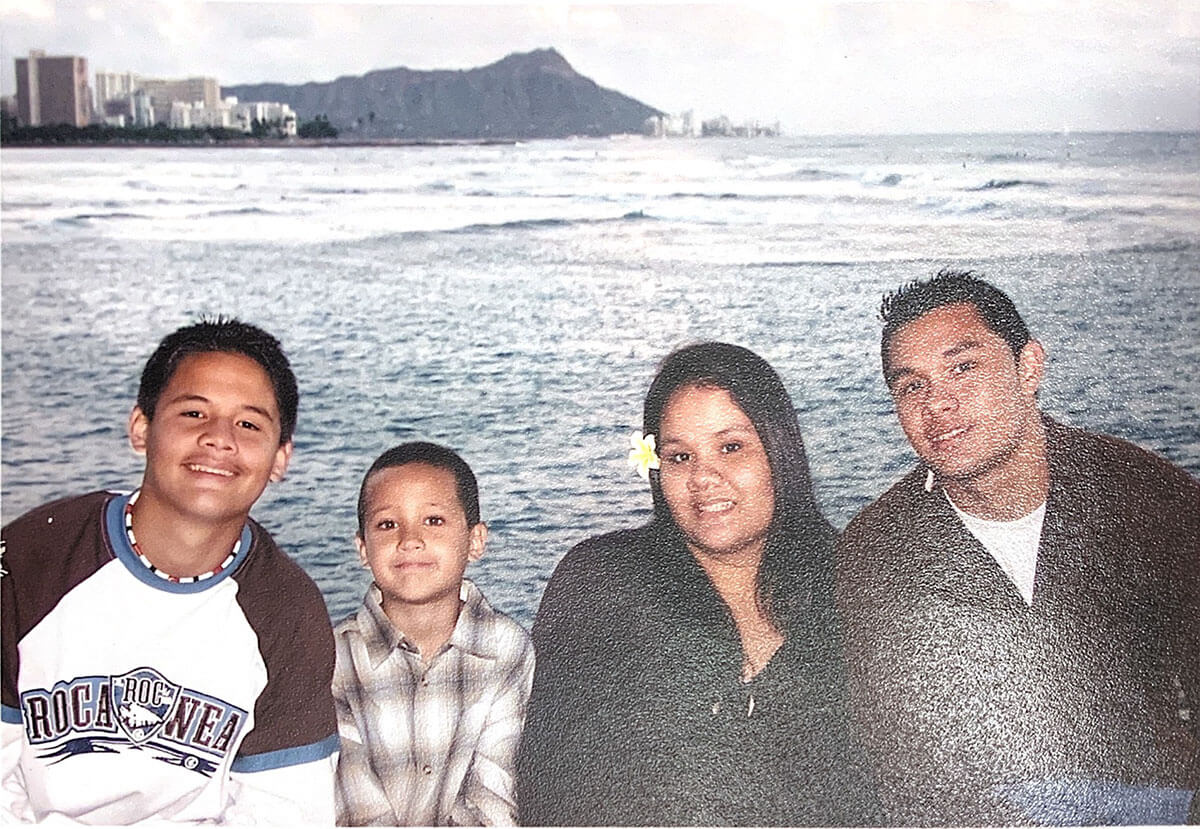

I was 5 when my brother came into our lives. Several days after he was born, his parents left him at our doorstep, packed their bags, and moved away with their two older children. Simply put, he was abandoned by his birth parents. Still, he was never truly abandoned because he was where he needed to be — in our family. Yes, my brother was technically my cousin, but he was hānai from birth by our family.

As you may know, the Hawaiian word hānai is often interpreted as adopted, but when translated, it means: to raise, rear, feed, nourish, sustain. To raise: as in the countless times my sister sat with him and helped him with his homework, patiently teaching him how to read and write. To rear: as in those times I would hold his hand and walk him to school and basketball practices at Kīpapa Park. To feed: as in the food my older brother provided, forcing him to sacrifice his own childhood to help my mom around the house. To nourish: as in the love my mother lavished on this boy because she knew he was so desperately in need of love. To sustain: as in our family giving Alan all that we could so that he could thrive. We loved him because he was one of our own.

Although he knew he was not our biological brother, the subject was strictly taboo — a means with which my mother protected him from the heartbreaking truth of his parents not wanting him. “Grandma said that I had to take you” was the only answer he ever got. Anyone who was raised in close proximity could see that he struggled with the ambiguity of his place in our family. One could see that the question that plagued his heart was: “Why didn’t they want me?” I’ve come to refer to this abandonment as his childhood wound — a pain he bore and tried to make sense of his entire life.

As he grew older, Alan exhibited certain behaviors that I would attribute to this pain, this yearning to belong. In times of trouble, he would willingly sacrifice himself to belong to the crowd, often taking on the role of the garut.(1) His unwavering loyalty was maddening, but as I reflect on those moments, I realize that the desire to belong cultivated within him a heart of compassion and inclusivity. His pain allowed him to recognize and embrace that very same pain in others. Instead of inflicting harm and negativity, he willingly and courageously opened his heart and created space where people felt like they could belong.

I can’t quite describe how difficult it is that he is not here. Over the course of the last several months, my family has been dragged through hell and back. Surprisingly, the biggest source of pain came from within our own flock — family members, stricken with guilt and shame, forcing their way into the picture and attempting to erase us from Alan’s life. Meanwhile, there were other family members, who had no relationship with Alan, selfishly seeking to profit off of his death. It certainly has been a trying time. Yet the one thing that has been a consistent source of consolation is our faith.

A theological imperative that stands at the fulcrum of the Christian faith speaks of the incarnation: a single event in history when the Creator of the Universe audaciously yields Divine power and Being and takes on the form of flesh and sinew. The incarnation tells us of the Cosmic Embodiment of perfection and holiness; a God who humbled Themselves and exchanged Divinity for frailty and finitude, becoming one with Their Creation. The incarnation reflects a severe contradiction wherein the supposed Savior enters the world as a vulnerable infant — destined to take on a yoke of imperial subjugation, dehumanization, and more importantly, the pain of humanity — only to meet a horrific manner of death by murder.

For my own faith, the power of the incarnation is the binding of Divinity and woundedness. The biblical narrative tells stories of a Benevolent Creator, willingly taking on the physical embodiment of pain and suffering to forge a new path for healing and restoration. It is in identifying with our pain that the Messiah navigated the complexities of humanity and still made a conscious decision to model compassion, mercy, and love, which form the pillars of the Kin-dom. More importantly though, through Jesus, we see the ways in which identifying with woundedness begets an audacious posture of humility and forgiveness. This is exemplified in his greatest hour of distress. As Jesus hung on the cross, he looked upon his murderers and said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” Moved by compassion, Jesus recognized the entanglement of physical malevolence and inescapable woundedness. And although he was well within his power to declare judgement and death, he advocated for mercy and forgiveness.

“Forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”

Pain has been the abiding trait of humanity from time immemorial. Some people go through their entire lives avoiding and medicating pain. Other people, like Alan, choose to embrace it as a language of commonality and connection. I know this because it’s how our mother raised us. In her care, Alan allowed his deepest wound to transform into his greatest attribute: his abundant love for others.

I don’t know you. I’ve never met you. I know nothing about your life. But I don’t need to know you to know that the action of taking someone else’s life reflects deep, unbridled pain. And I’d imagine that at some point, that pain has amplified even more because you took my brother’s life. I acknowledge that pain.

I share my brother’s pain with you because I can imagine something in his story might resonate with you — whether that’s rejection, neglect, abandonment, or a desire to belong. I must confess that I am no clinician, but I’ve lived and worked with people long enough to know that our childhood wounds shape us. They mold us; they form us. And when left unattended, those wounds fester, and we navigate the world projecting our pain onto others. It reminds me of the old adage, “Hurt people hurt people.”

Although there are times when I experience deep sorrow and grief at how Alan died, I can stand confidently and say that I don’t think you’re innately evil. You are human. You are wounded, just like the rest of us. However, if you saw the world through my eyes, you would know that you were created to be so much more than your pain. And I believe, without a shadow of doubt, that your pain deserves healing and restoration. You deserve healing and restoration.

I want you to know that I pray for you and your family. I want you to know that my family prays for you and your family. And I want you to know that my mother prays for you by name. She asks God to help her love you like she loved her own son.

It is understood that the scriptures instruct us to pray for our enemies, but you are not our enemy and our prayers are not motivated by pity. We pray for you like we prayed for Alan. We stand in the gap for you, like we stood in the gap for Alan. We fight for you, like we fought for Alan. We intercede for you — asking the Spirit of Peace to envelop you in a love that silences disillusion and declares that you are still worthy.

To the man who murdered my brother,

I forgive you.

I hope that one day you will be able to read and receive this.

And I hope that one day, you will be able to forgive yourself.

(1) Hawaiian Pidgin (Creole English): meaning sucker, peon.

Brandon Tacadena is a Master of Divinity candidate currently attending Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York. He was born and raised on the island of O’ahu, in Hawai’i. Brandon has genealogical ties to Sāmoa, Tokelau, the Philippines, The Cook Islands, and various parts of Europe. Tacadena’s work explores the intersections of theology, colonialism, spiritual fluidity and Pasifika indigeneity.