The Khmer Rouge was a brutal communist regime that sought the ethnic cleansing and violent reordering of Cambodian society in the 1970s. An estimated 2-3 million Cambodians died in the regime’s prisons, labor camps, and killing fields, a tragedy now known as the Cambodian Genocide. Tens of thousands of families were separated, including this one.

Reunion

On a sweltering hot day in April 2018, Friar Unly Son (Son) was making last-minute preparations to welcome Unly Sat (Tao) and his family to Cambodia. Son was constantly on and off the phone with Tao, trying to determine the approximate time of their crossing from Thailand to Koh Kong, Cambodia. The air was filled with urgency and anticipation, and the border swarmed with a sea of people as traders pushed fruit carts and other merchandise before the border closed at 5 p.m. Son and his family buzzed with excitement and expectancy.

After all, Tao and Son were twin brothers, and they were planning to reunite in their native Cambodia for the first time in 42 years.

Fleeing Cambodia

Son and Tao were born in October of 1961 in Cambodia and grew up on a farm in Kop-Thom, a village near the Thai border. Although they were not rich by any means, they had enough to live. But in 1975, when Son and Tao were 14 years old, the Khmer Rouge took Cambodia and captured Kop-Thom.

Their family was moved to a labor camp. Eventually, Son joined a group of people that escaped to a village in Thailand — an escape that separated Son and Tao from each other and from the rest of their family. Son would not see Tao again for more than four decades.

Finding Survival

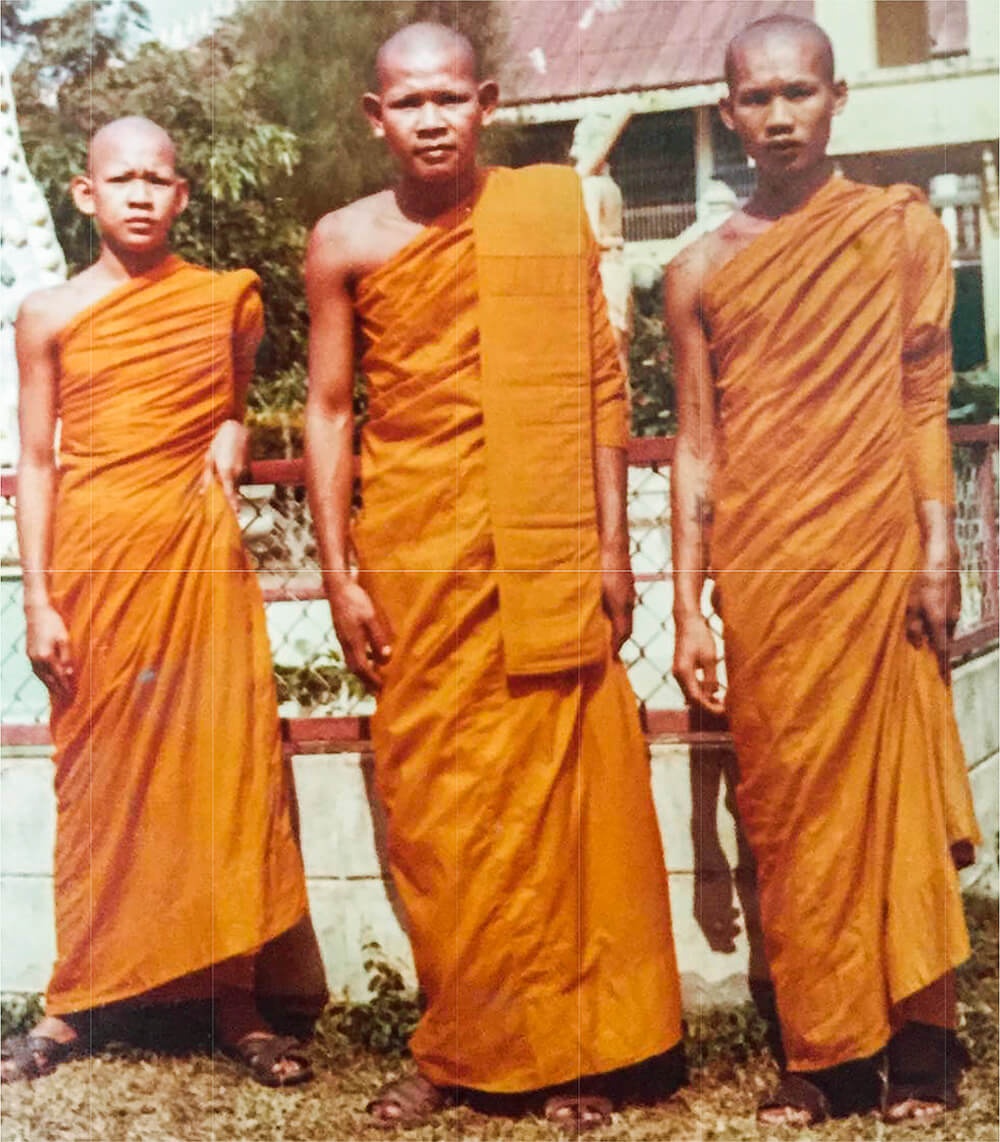

After arriving in Thailand, Son searched for his aunt, uncle, and older brother who had already been living there. Son was relieved when he found his older brother, a monk, at a Thai Buddhist pagoda.

The war had thrown Son’s life into uncertainty, with constant movement and emotionally-draining separation from his family. Amid the chaos and violence, Son saw what he calls the “possibility of a stable life with room and board” at the pagoda. At age 15, he decided to join his older brother and become a monk.

Tao did not find stability so quickly. Instead, he spent the next four years separated from family until Tao’s father found him in Sisophon and brought him back to his mother and sister in Neameat. “I was very happy to see my parents and sister”, says Tao. “I thought that I would never see my family again.” The four of them crossed over to Thailand to stay in a refugee camp. But their refuge was short-lived: After just two weeks, the Thai government returned refugees back to Cambodia, and Tao, his parents, and his sister were placed into another camp by the Khmer Rouge.

Provided with only soup, Tao and his family often went hungry and had to search for food outside the camp. One day, Tao and his mother crossed the border to a small Thai village to buy rice. While they were there, a Thai farmer offered Tao a job on his farm that included room, board, and pocket money. Having lived through six years of uncertainty from the war, Tao, like Son at the pagoda, recognized the possibility of a stable life. With a heavy heart, Tao asked his mother to return to Cambodia without him. Tao was 19 years old when he became a farmer.

Expanding Families

Son and his two older brothers received word from their uncle, who sensed continued uncertainty from the war, and advised them to move from their pagoda to a Thai refugee camp and apply for refugee status in Canada. Son and his brothers took their uncle’s advice, moved to the refugee camp, and applied for refugee status. Within two years of leaving the pagoda, Son and his older brothers had been accepted to Canada. Upon departing for Montreal, they still had no information about their parents, Tao, or their younger sister. “It was painful to leave”, recalls Son. “Not knowing about Tao was not easy.”

Son did not like Canada at first. “It was cold, and I did not understand the culture and the French language”, he remembers. But his transition was eased by his Canadian host family, who sponsored him by providing food and housing. By March of the following year, Son’s birth parents and younger sister also arrived in Canada as refugees. Son now had two sets of parents and siblings in Canada and was overjoyed to receive them. Still, he was dismayed that Tao was absent from his new, larger family.

Unbeknownst to his family in Canada, Tao was setting up his life in Thailand. Tao learned the Thai language and recalls, “I enjoyed working on farms and the owners treated me well.” One day, as Tao was working, he saw a beautiful Thai woman who had come to fetch water from a well. Tao helped the woman and found out her name: Dao, which means beautiful in Thai. Dao often returned to the well, and their friendship grew over time. Eventually, Dao’s family invited Tao over for a courtship visit.

Dao’s family liked Tao and asked him to meet Dao’s father. After Tao met the father, the family checked Tao’s character references. The owner of the farm provided his reference and informed the family that Tao was an orphan and spoke good Thai. No one knew that he was Cambodian — a fact that was crucial for Tao, who feared that he would be deported if anyone around him came to know that he was Cambodian.

Upon hearing the good reference, the family accepted Tao’s proposal to marry Dao, and they were married in August of 1982, two years after he had separated from his family to work as a farmer. Separated from his true family and thought to be an orphan by Dao and her parents, Tao entered a new family through marriage.

Shifting Identities

Tao did everything possible to be perceived as Thai: he chose to not be in contact with any Cambodians around him and devoted all his time to family and work, never telling anyone — not even Dao or their children — about his former life or true identity. Like the decision to accept the very first farming job, it was a move Tao made in order to survive.

In adulthood, Son’s identity shifted, too — this time in a religious sense. As Son learned about Christianity in Canada and was invited to family prayers by his host mother, he developed an internal conflict. “I wanted to know Christ, but wanted to remain a Buddhist”, he recalls. In Christianity, Son found a sense of place, even as someone who had been displaced over and over again as a refugee. Son’s host parents encouraged him to explore a local catechism class, and after a priest spoke with Son to make sure that he was pursuing Catholicism of his own free will, Son began attending the classes. At age 23, after studying catechism for two years, Son and his younger sister became Catholic.

For the rest of his twenties, Son began to sense a calling to the priesthood. At age 27, he learned about the Catholic Church in Cambodia from Cambodian priests who came to Montreal with the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Three years later, the Paris Foreign Missions Society sent him to a seminary in Vienne, France, to study for a year. But first, Son returned to Thailand in search of Tao. When he did not find Tao, Son went on to study in France, but did not give up looking for his twin brother. In 1992, he decided to continue with his studies in Cambodia, where he made continual radio announcements about his search for Tao. Upon completing six years of study at the Battambang Seminary, and 25 years after he had become a Buddhist monk, Son was ordained as a Catholic priest. All the while, he did not give up looking for Tao.

But Tao could not be found, as he continued to conceal his Cambodian identity to avoid the possibility of deportation. Even as late as 2010, when some Cambodians came to work in Tao’s area and spoke his mother tongue of Khmer, Tao responded only in Thai. For Tao, the legacy of war was fear.

Brothers Reunite

In January 2017, Son received a call from an old friend who told him that a mutual friend had Tao’s phone number. Son remembers the day well. “January 7th, 2017 was the longest day in my life”, he says. Son waited the whole day for Tao’s number, and as soon as he got it, he dialed Tao’s number. Son remembers feeling a medley of anxiety and joy as Tao picked up the phone, and telling Tao that it was his twin brother calling. Tao instantly recognized Son’s voice. The twins cried upon hearing each other’s voices for the first time in 42 years, and spoke to each other for a long time.

Soon after the phone call, Son went to see Tao in Thailand. Upon arriving, they entered a taxi whose driver immediately recognized that Son was not Thai. Tao hesitated to embrace Son, still fearing that his Cambodian identity would be revealed.

Tao took Son to his home, where his wife and two teenage children were waiting to meet their uncle. As the family celebrated the reunion of brothers over several Thai meals, Tao’s family found out for the first time that Tao was Cambodian. At first, his wife and children did not believe him. All those years, they had thought that he was a minority Thai Laotian. It was a revelation that Tao had feared for so long, but now brought him relief.

Family, Lost and Found

On that sweltering hot day in April 2018, Son and his family waited by the Thailand/Cambodia border among the merchants and food carts that darted by. But they were unconcerned with the clamor — they were looking for something much more important, something they had waited for for decades. Along with the humidity, a 43-year family history splintered by war hung in the air, ready to be reconciled.

Though they spent more than four decades and 4,000 miles apart, Son and Tao’s lives seemed to mirror and magnetize each other as they found new vocations, new families, and new identities in a journey of survival that began when they were 14 years old.

“We never heard from each other during those years and my family thought that [Tao] had died”, recalls Son. “But I had the feeling that he was still alive. I never stopped searching for him and never wavered in my faith. I believed that someday God would unite us. Indeed, God never fails. Like a shepherd who cares for his sheep, if one is lost, he would do his best to find it and hold it in his arms.”

Finally, dressed in beautiful Thai shirts and dresses, Tao and his family emerged from the crowds of people. Son was the first to greet them with kisses and hugs. Family and friends followed with cold water bottles in their hands as they drove to the local church to celebrate with a sumptuous feast. Every word, every touch exuded joy.

After resting, the family and friends drove to Chamkartieng Village, where the twins’ 94-year-old mother lived. Upon arrival, Tao was first to get out of the car, and he rushed to greet his mother. He bowed to her feet in the traditional Khmer way and started crying. The mother gingerly picked him up and held him in her arms for a long time. As they hugged and kissed each other, Tao was introduced to the villagers who welcomed him. As the village community began to celebrate the reunion of the twins, Son was reflective.

“What else can I say, what else can I ask for?” he asked. “Nothing more.”

Andrew Jilani is a Catholic from Pakistan. He holds a doctorate from the Center for International Education at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He works in developing countries designing and implementing basic education projects for refugees, girls, and in improving Early Grade Reading and in strengthening host governments’ education systems. He learned Vipassana meditation in Sri Lanka and practices yoga. He is currently based in Cambodia.