I recently moved to New York for my first job. For the first time in my life, I am somewhat financially comfortable. Yesterday, a direct deposit into my savings account made me feel independent and safe from having extra money sitting around. Then I remembered my parents don’t have enough for retirement. My mom recently told me that they never saved money before and we basically lived check to check my whole life. She called that “trusting in God”.

My new job is in the Bronx. Every day, I am confronted with the reality that I am well-off by certain standards. My commute to work consists of the bus driving past the Bronx judicial courts and seeing majority Black and Brown folks streaming through the doors due to over-policing. There was a day at work where I pushed social media on a study that found that low-income folks get criminalized for fare evasion — basically, criminalized for poverty and not being able to afford $2.50 to ride the bus or subway. After work that day, an Asian American police officer let me jump the turnstile because it looked like I was having a hard time finding my MetroCard. I said “thank you” and felt guilty, but nevertheless thought it was my lucky day.

On every second Friday morning, I get paid more money than I’ve ever had. I love my job (another luxury) because I am proximate to the people and needs I feel are most important. But I can’t help but feel wrong for jumping into their lives from my level of comfort.

• • •

Since college, I’ve tried to prove my conviction for equity by living as ethically disciplined as possible. This was driven by a guilt for going to a predominantly white, evangelical, liberal arts college — despite being on financial aid, taking on debt and struggling with multiple issues with the institution itself. I boycotted large corporations of all kinds such as Zara and Forever 21 because of sweatshop labor. I refused to eat at McDonald’s or any fast food chains that profited from suppressing farmers’ rights and monopolizing food. I transitioned to buying from local farmers markets every weekend, even if it cost me more and required me to work extra hours at my part-time job. I picked churches or refused to go to churches that did not affirm the “least” in society. I attended every protest possible. My social media became dedicated to these issues. Most importantly, though, I got organized and joined organizing groups.

However, after years of being driven to act primarily out of guilt, I became worn out. I found myself arguing one night with my best friend, a South Korean immigrant woman, over a Tim Keller sermon about entitlement. I heard myself, in a sort of out-of-body way, being divisive rather than building bridges. After we hung up, I realized that I could not keep on hating myself anymore, because it was beginning to seep out. I was beginning to hate every little thing in people I found wrong. Hating people, instead of systems, is no way of building a collective movement. That night, I found that if I was yelling at a woman with similar experiences as me, then I was sorely lacking the same empathy I espoused when I was trying to fight for the marginalized.

Like in my faith, guilt transformed into a tool of self-oppression. I experienced privilege the same way I experienced sin — something I inherited, was inherently so, and had no control over being. Both privilege and sin were ingrained in my flesh — they still are, and I need to continuously fight and die to them. However, unlike sin, there seemed to be no forgiveness from privilege. I could not change the history and race I inherited. It became a continuous, never-ending process of self-flagellation every time I saw another news article on my Facebook, another homeless person I didn’t make eye contact with, another day at work in the Bronx.

• • •

Guilt is an intensely conservative emotion. Perhaps evangelical white Christians react strongly against criticisms of privilege because of how laden it is with guilt. It is a burden that only gets heavier without a savior. In that sense, I relate to it. It makes you want to give up, deny the problem altogether, and fall back into what’s comfortable and easy.

However, I’ve come to find that experiencing guilt is highly important, as long as we move beyond it and into liberation. James Baldwin once said, “I’m not interested in anybody’s guilt. Guilt is a luxury that we can no longer afford. I know you didn’t do it, and I didn’t do it either, but I am responsible for it because I am a man and a citizen of this country and you are responsible for it, too, for the very same reason.”

Baldwin’s quote relieved me, because for first time I was given permission to let go of self-hatred. Previously, I did not have the right to self-pardon and was desperate for someone to give me that to me.

No one wants to hate themselves for something they cannot control. It is important, however, to remember that if we do nothing in the face of these systems, then we are guilty. The shift from guilt to responsibility freed me to live well, which is especially important as a woman of color. I am reminded by Audre Lorde that self-care is especially important as a first-generation woman of color: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” Guilt had become a tool to tear me down rather than uplift me to move forward, and this had become a form of internalized oppression.

The other day on the bus I saw an old Black man using an oxygen tank. I noticed that he had a Black Panther tattooed on his forearm. Rather than immediately jumping to thoughts such as “I’m not doing enough” or “I’m not meant to be here”, I experienced a certain unspoken camaraderie with him and was inspired to tackle the future due to people like him who have resisted in the past.

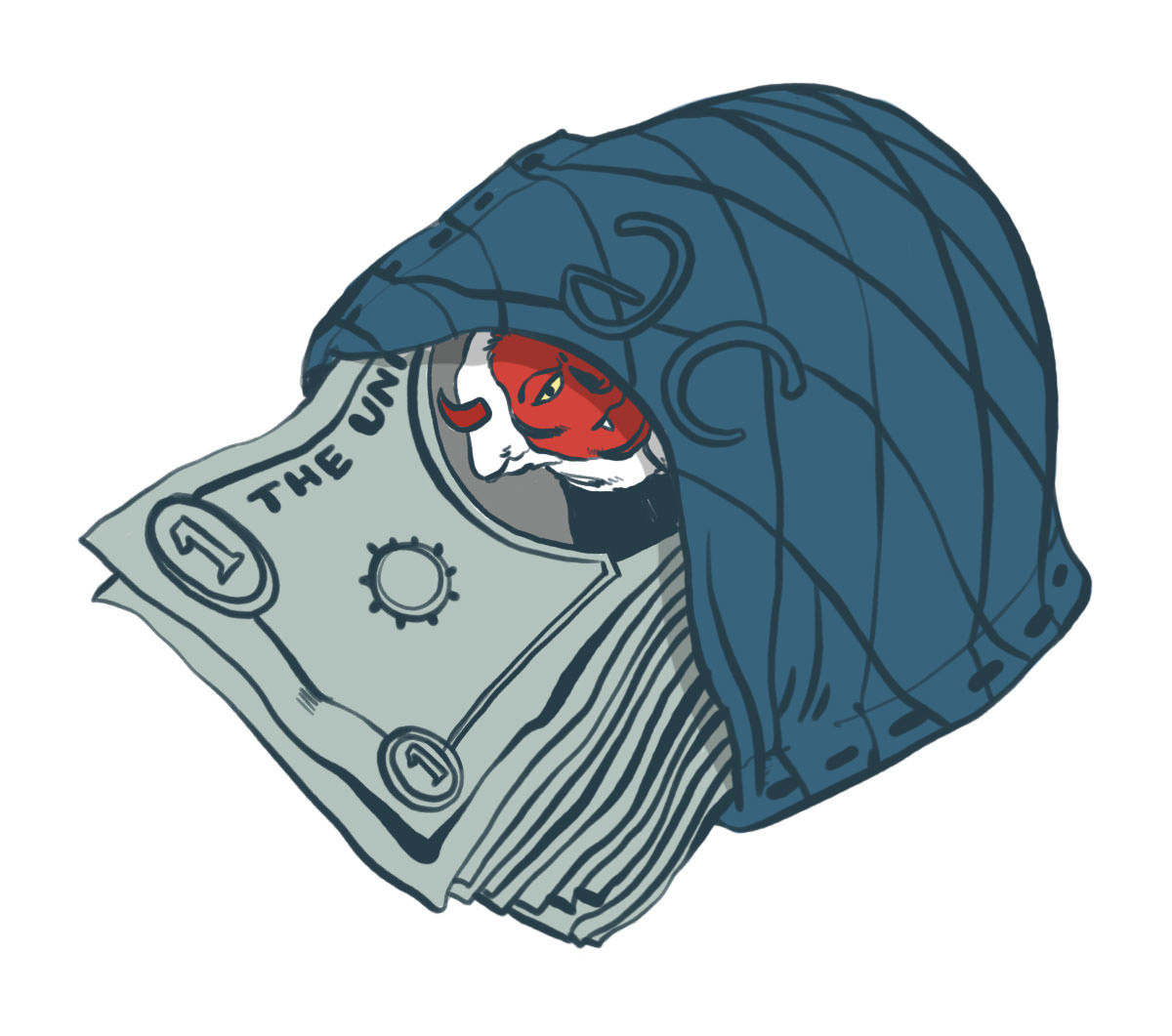

It is still important to live as ethically and radically as possible daily, especially if you’re in a certain class and race. Redistributing wealth and tithing as a habit are crucial because, unlike the privileges of race and gender, class is something you can choose to give up. I still try to do everything I’ve been doing since college, but instead of feeling inadequate every time I contribute or don’t contribute enough, I thank those who have come before me for allowing me to be where I am today. The urge to constantly prove that I am sorry for what I have or who I am is replaced with gratitude. When I feel simple happiness, it is redirected outwards rather than inwards — from guilt to a recognition that everyone should be able to feel this level of financial security and have this livelihood, too.

Chinhsin Esther Kao is Bunun-Taiwanese and a first generation immigrant to the U.S. She currently works at The Bronx Defenders as their Communications Associate. Outside of work, she is a Progressive Asian American Christians fellow and organizes with AF3IRM (Association of Filipinas, Feminists Fighting Imperialism, Refeudalization, and Marginalization).

Ellen P. Lea is a Floridian artist who specializes in conceptual illustrations based on society, portraits, cover designs, and viz-dev. She loves food, dogs, and her two beautiful younger siblings. Although her days are busy, she enjoys contributing to great causes with her illustrations when life needs them. She finds Inheritance magazine an inspirational part of her life due to her once being a lost, questioning soul herself, who now has found her true self. You can find her at: ellencreative.com.