I am pleased by this invitation from Inheritance magazine to reflect on the concepts that were powerful for me in understanding my identity as an API Christian. I begin by doing a riff on the prevalent stereotype of APIs as “model minorities”. I am an “anomalous” minority. Unlike most APIs that I know, I was raised in the slums of Chicago with playmates who were Black and Puerto Rican. When an API friend asked me if any of my female friends growing up had their “eyes done”, I had to respond, “Say, whaaat?” I only encountered whites (and racism) when my family moved to a white neighborhood, which soon became Black because of white flight. Unlike the stereotype, I am terrible at math and science. I withdrew from algebra three times before I flunked out. I barely got on the lowest scale for my math GRE (Graduate Record Examination). My misadventures in chemistry are too long to relate. I therefore had to abandon my pre-med major and switch to English Literature in college.

Unlike many APIs, I was fortunate that my parents did not force me to get As or even do well in school. They were too busy supporting and raising 12 children, of which I was the oldest. What therefore developed in me was a curiosity and love of learning on my own. When my family moved to that white neighborhood, the grade school I attended had “homogeneous” groupings. In descending order, Group 1 supposedly contained the most intelligent and talented, and Group 4 was deemed the “dumb-dumb” group. I was put in the latter. However, I saw at the tender age of 10 that the individuals in Group 1 were all white and that Group 4 contained the racial/ethnic students and those white kids who were regarded as “trash”. This experience sowed the seeds of my racial consciousness in a white dominant society. In spite of being in the “dumb-dumb” group, I was the first in my family to go college. The main reason I did so was to escape from a house that had only one bathroom for 13 people. A secondary reason was to progress in that love of learning at an advanced education institution.

As a third-generation Chinese American, I was not able to draw on my parents’ immigrant experiences of China, since they were not immigrants themselves. Although they did speak Chinese, they did not teach any of us; I suspect this was so they could gossip with our relatives without us understanding what they were talking about. I also have to admit that my knowledge of what was Asian was mediated by American Orientalism: the representation of Asia as a geographically distant, foreign land filled with exotic and questionable characters and cultural practices that must be subdued and domesticated. My early exposure to things Asian was through Charlie Chan and Pearl Buck movies, where white actors played Chinese characters. My Chinese icons were Fu Manchu, Dragon Lady, and Ming the Merciless from the planet Mongo of the Flash Gordon TV series.

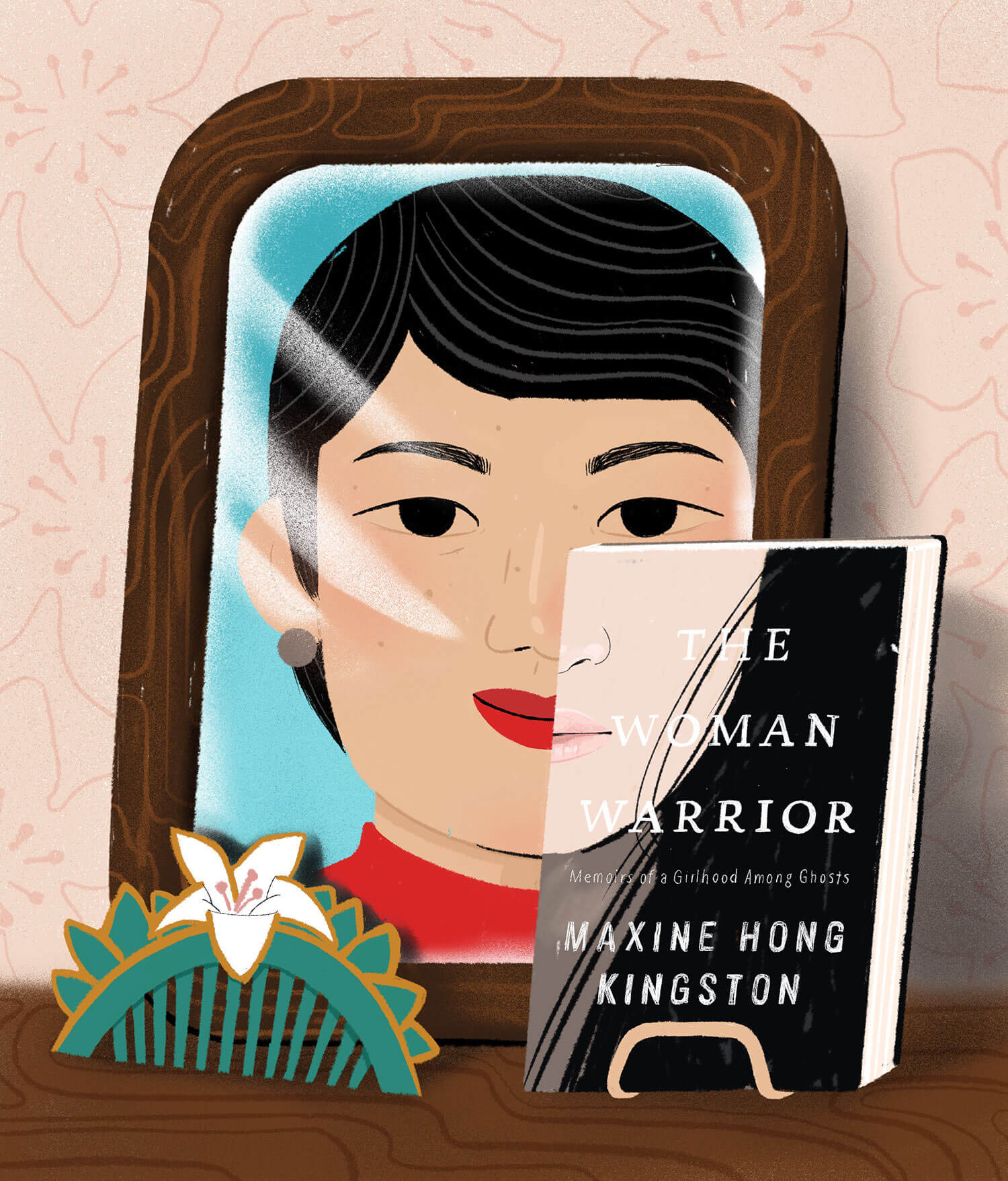

There was one icon, however, who made an impressionable mark on me. In 1977, I saw Maxine Hong Kingston’s “The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts” in a bookstore. I only actually read the book when I had to teach it in a Women in Literature and Theology course in the late 1980s. I was much more intrigued in my late 20s by the concept of a woman warrior in the legends of the Chinese. I was fascinated by a strong, indomitable character who broke the traditional stereotypes of submissive Chinese womanhood, who knew the martial arts, and was, like me, Chinese. Here was a fighter against injustice and evil who would become an avatar for me in my own confrontations against the inequalities of the world. Because of my captivation by the concept of a woman warrior, I embarked on a study of a woman warrior in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, the assassin Jael in Judges 4, as well as a cross-textual investigation of Jael and Fa Mulan, the woman warrior who inspired Kingston’s book.* In spite of the fact that Disney’s Mulan is another example of American Orientalism, transforming the ancient Chinese legend heroine into a Western animated family film for the global market, I still wish that I could have seen a film like this in my early childhood years. It would have made a positive mark on my racial formation in seeing a spunky independent teen searching for her true self. In contrast to other Disney films, Mulan was able to save the male hero, rather than being saved by him, and rescue the emperor and his kingdom from the Mongol conquerors as well. She defied the Disney stereotypes of heroes.

Another important aspect of my identity is that I was raised Roman Catholic. I point this out because the Christian APIs I usually encounter are Protestant, many of whom are evangelical. Unlike Protestants, I am not bound by their doctrines of biblical authority, particularly in debates in the public square on the use of the Bible in social and ethical issues. Although I am a devout Christian, I study the Bible primarily as an academic. Although a beautiful and spiritually inspiring text in many ways, I know that it is also sexist, ethnocentric, and violent. And its sexism, racism, heterosexism, etc. has legitimated violent wars, conquests, colonization, and sexual and domestic violence over the course of history. As a biblical scholar, I approach my interpretation of the biblical text rather like a woman warrior in asking the ethical question, “Whom does my interpretation help, and whom does it hurt?”

The Chinese concept of the woman warrior has been very formative in my own identity as an “anomalous” API Christian. It resonated with my own independent spirit in my educational advancement from grade school all the way to my Ph.D. and in my biblical scholarship. The woman warrior will continue to be my avatar as I continue to fight injustice and work for a compassionate and shalom-filled world.

* Gale A. Yee, “‘By the Hand of a Woman’: The Biblical Metaphor of the Woman Warrior,” Semeia 61 (1993): 99–132; Gale A. Yee, “The Woman Warrior Revisited: Jael, Fa Mulan, and American Orientalism,” in Joshua and Judges, ed. Athalya Brenner and Gale A. Yee, Texts @Contexts (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2013), 175–90.

Gale A. Yee is Nancy W. King Professor of Biblical Studies emerita at Episcopal Divinity School. She is the author of several books, as well as many articles and essays. She currently lives at Pilgrim Place, a retirement community in Claremont, California, known for its social activism.

Kimberlie Clinthorne-Wong is an illustrator and ceramic designer based in Hawaii. She is the cofounder of the collaborative ceramics studio, Two Hold Studios, LLC. Kimberlie’s work can be found at www.kimberliewong.com and on Instagram @kimiewng.