As the debate takes shape, Ken learns what it means to lay down his position of power and privilege, and the fine line between dialogue and monologue.

A few months after my January 2007 dream and shortly after my church board had decided to join me in risking our reputation, I began to meet with the Christian social justice group who spearheaded the debate on homosexuality.

Each month, seven to 10 of us would squeeze into a cluttered conference room in Little Tokyo to work out the details of this unprecedented Asian American Christian event. We agreed to have it on a night in May of 2008, and as we started to work out the other details, we realized that our most pressing concern was coming up with an openly gay Asian American Christian to be my debate opponent. We not only needed someone who would risk speaking openly and proudly about being gay in front of a predominantly straight and nonsupportive audience, we also needed someone who would let me confront his convictions. Not many people came to mind.

As we talked about it, one person on the planning committee suggested Melvin, who’d served on my pastoral staff for over a decade before leaving for another pastoral job at an evangelical church in the Bay Area. He and I had been good friends for more than thirty years, so we thought he might be willing to be on stage with me. As far as any of us knew, he’d always been a celibate gay man, and we were confident he would reinforce what we all believed. However, we couldn’t overcome one complicating factor—he had yet to publicly admit to being gay. That made it hard to invite him!

Once we decided Melvin wasn’t a good option, the chairperson of our group asked, “Okay, what about Gary?”

I first met Gary in the late seventies after I had started dating one of his good female friends, who later became my wife. Early on, I asked her if she thought Gary was gay. She just raised an eyebrow and said, “What do you think?”

Gary was a graphic designer and we later asked him to design our wedding invitations and sing at our ceremony. He eventually decided to attend Fuller Theological Seminary’s School of Psychology and later became a highly respected marriage and family therapist. I got to know him much better a few years later, when we brought him on staff at our church as our part-time worship leader.

Several years went by and our church grew because of the intimate worship that Gary’s anointing and giftings had brought us into. One day during a staff meeting, Gary shared that he had recently confessed to being attracted to other men while going through a sexual healing ministry. He told us, “I’ve never acted on these impulses, but I’ve been battling them most of my life. I have a ‘father wound’ as a result of what I now see as my father’s emotional abuse of me. But through much prayer, my Heavenly Father is filling that hole in my masculine identity.”

We supported him wholeheartedly, and with the entire staff’s blessing, Gary boldly preached about this over the course of several Sundays, proclaiming the healing power of God in the face of his sexual brokenness. We extolled him for his courage and unshakeable faith in the Lord’s healing power. Still, I privately I wondered if all this meant that God was transforming Gary into a heterosexual, especially since Gary seemed just as gay as before. With so many celebrating his public repentance from same-sex attraction, I felt as if I would be accused of blasphemy for sharing my doubts, so I only dared to share them with my wife. I quickly found out that I wasn’t the only one questioning his becoming straight.

Gary left our staff a few years later to be a chaplain for the Vineyard’s burgeoning “Desert Stream/Living Waters”, an international ministry to the sexually shattered and addicted. His prayer letters were filled with glowing reports of how God was using his testimony as an “ex-gay” and his teachings to restore many others, including numerous gays. A few years into his ministry, however, he quietly reversed his convictions. While he continued to minister to those struggling with sexual sins, he surreptitiously believed that God had created him gay and loved him exactly the way he was. When he finally divulged this to his teammates, they were appalled and disheartened. Since he could no longer serve in this ministry with integrity, he returned to Los Angeles, determined to carve out a new life as an openly gay, non-celibate Christian.

I wasn’t thrilled about the idea. I told the chairperson that I would reach out to Gary, but the prospect of it really challenged me. When Gary had been “gay-condemning”, as a community we couldn’t laud him enough for being a role model for how other Christians should respond to having same-sex attraction. But when he came home “gay-affirming”, most of us abandoned him, quickly obscuring his contributions to our church’s growth and reputation, conveniently ignoring that he was now a defiantly gay Christian.

In the ten years since Gary had been back in LA, I had occasionally referred some counseling cases to him, but I had also avoided asking him why he reversed his position on homosexuality. As a result, I felt really uncomfortable asking him to debate me publicly on the matter. Nonetheless, I arranged for a time to go to his cozy South Pasadena counseling office to ask him in person. He invited me in and showed me to the upholstered chair where his clients normally sat. Even though I was only eight feet from him, I could feel the vast relational distance created by a decade of mutual aversion and avoidance. It was too tense for small talk, so I immediately began unpacking the purpose of my appointment.

“The reason I’m here, Gary,” I explained, “is to invite you to be my debate opponent on the issue of homosexuality and Christianity. Some Asian American Christians are putting together an evening next year in May at my church to break the unbearable silence on this issue. And we were wondering if you would help in airing out our differences that night.”

I can still remember how his lower jaw stiffened as he replied, saying something to the effect of, “Now why would I want to do that? What would be the point? I already have new gay-affirming friends, a new gay-affirming church, and my new life as a proud gay man. Why would I want to enter a debate about who I am? Keep looking.”

His response took me by surprise and I immediately wondered if he was right and if staging the debate was a mistake. I realized that typical debates on this volatile issue are more like serial monologues than actual dialogues. One side spells out why their point of view is more authoritative, while the other side, pretending to listen, is actually preparing counter arguments to invalidate what’s being said. At the conclusion, neither side learns anything new or valuable from the other because neither one ever intended to listen nor learn.

A debate suddenly seemed to directly contradict the biblical mandate for Christians to be “quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry” (James 1:19 NIV).

I took a deep breath and decided to adjust my course. I answered him. “Your distaste for debating me struck a chord. A debate can’t possibly move us from where we’re all stuck. But a respectful conversation modeling “convicted civility” might.

He asked me to elaborate. So I continued by saying, “The world needs more people who hold deep convictions. As evangelicals, our convictions should be rooted in God’s Word. But reading the same Bible doesn’t produce Christians with identical convictions — the history of the Church is proof of that. Since we can’t send those who don’t share our convictions to the dark side of the moon, we must all at least embrace the conviction of civility so that everyone, even opponents on these issues, can coexist peacefully. What if our aim that night is not to debate each other, but to have an honest, mutually respectful conversation in public?”

Still, he was uncomfortable. He retorted, “I’ll do this on one condition. I want Marian to be up there with us. When I came back to LA, she was one of my few old Christian friends who really wanted to get to know and love me as a gay man. She’s my hero. I trust her. If you can convince Marian to do it, I’ll do it.

Marian was a wife and mother, a leader in my church, a Christian therapist, and also a really good friend. So I knew that she had become a fierce ally of LGBTQ people, but she purposely kept that under wraps. She was afraid of what others at church would think of her if they knew how progressive she was. Gary also knew how reluctant Marian was to go public with her views, so I wondered if his insistence on her joining us was his way of guaranteeing that he would be off the hook.

Still, I agreed to Gary’s condition, and together we convinced Marian to join us. By default, the three of us became the planning team for the substance of the event, so we decided we should meet at Gary’s office twice a month to prepare. I thought we were merely going to focus on how we would pull off this civil conversation in the face of differing convictions, but I was also looking forward to the chance to rebuild the necessary level of trust with Gary. I didn’t expect that we needed to address much else.

At one of our first meetings, I was completely caught off guard when Marian firmly declared that she wasn’t sure that she could stay at our church if someone like Gary wasn’t welcome. Internally, I went into shock. “I had no idea that I might lose valued straight members over this,” I thought. “Who else at our church feels like she does?”

I also realized, though, that if I were to rebuild trust with both her and Gary, I would have to be honest with them, even if they didn’t like what I had to say.

“Look,” I said, “I believe that the Bible teaches that homosexual behavior is sinful.” I saw them both stiffen up, but I kept going. “However, I’m not convinced that most persons choose to be gay. I certainly don’t remember choosing to like girls. But I do remember choosing to follow Jesus and so should every gay person who identifies as a Christian. That choice to follow Jesus is a choice to pursue a holier life. Christians are no longer free just to do whatever we feel like doing. We’re all bondservants of Christ. That means many things for straight Christians. And one thing I believe it means for gay Christians is a lifetime of celibacy.”

As they pushed back vigorously, I began to doubt that we could actually pull off a respectful conversation by the time the debate rolled around next year. Many of our subsequent meetings also ended up turning into intense debates, with them typically agreeing that I was wrong. I did not know how in the world we would avoid turning our event into an uncomfortable and contentious public quarrel.

We continued to meet, and one day I was inspired to offer them an alternative. “Doesn’t it make total sense that Jesus wants us to learn how to build real bridges of trust with each other before we can hope to model true convicted civility on stage?” I asked. “I’m going to stop defending my position so much and become a more empathic listener. My new goal is for both of you to feel that I understand where you’re coming from, even if I don’t agree with your positions or conclusions.”

That decision changed everything. Over the course of our remaining times together, I did my best to honor my promise and build a trust-bridge through listening to them empathically. Little by little, meeting by meeting, as they began to feel more understood, they started to extend that same remarkable grace to me. When the night in May finally arrived, a miracle had happened. We stepped on that stage honestly caring about and trusting each other.

We had called the event “We Need to Talk”, believing this title would frame the evening as more of an honest conversation than a debate. But the title was also meant to hint at the growing need to come together to rectify the ongoing stalemate between traditional and gay Christians. Since we didn’t have an advertising budget, none of us really thought that there would be a huge turnout. We were wrong.

Half an hour before we were going to start, I watched as my former boss, an extremely conservative senior pastor, started leafing through the handouts that I had allowed two leaders from the local Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) group to display on the six-foot tables in the back of our sanctuary. I knew that he was going to be quite upset at the paucity of materials from a conservative Christian point of view. I comforted myself by remembering that we had agreed this was not going to be a debate, so it wasn’t a priority to present a perfectly balanced argument on the tables or on stage. Still, knowing that he was there and getting peeved dredged up all the misgivings I’d had over the previous months. Including the PFLAG leaders, who were to join us onstage and share their journey as Christian parents in learning to accept and love their lesbian daughter, I would be “outnumbered” four to one.

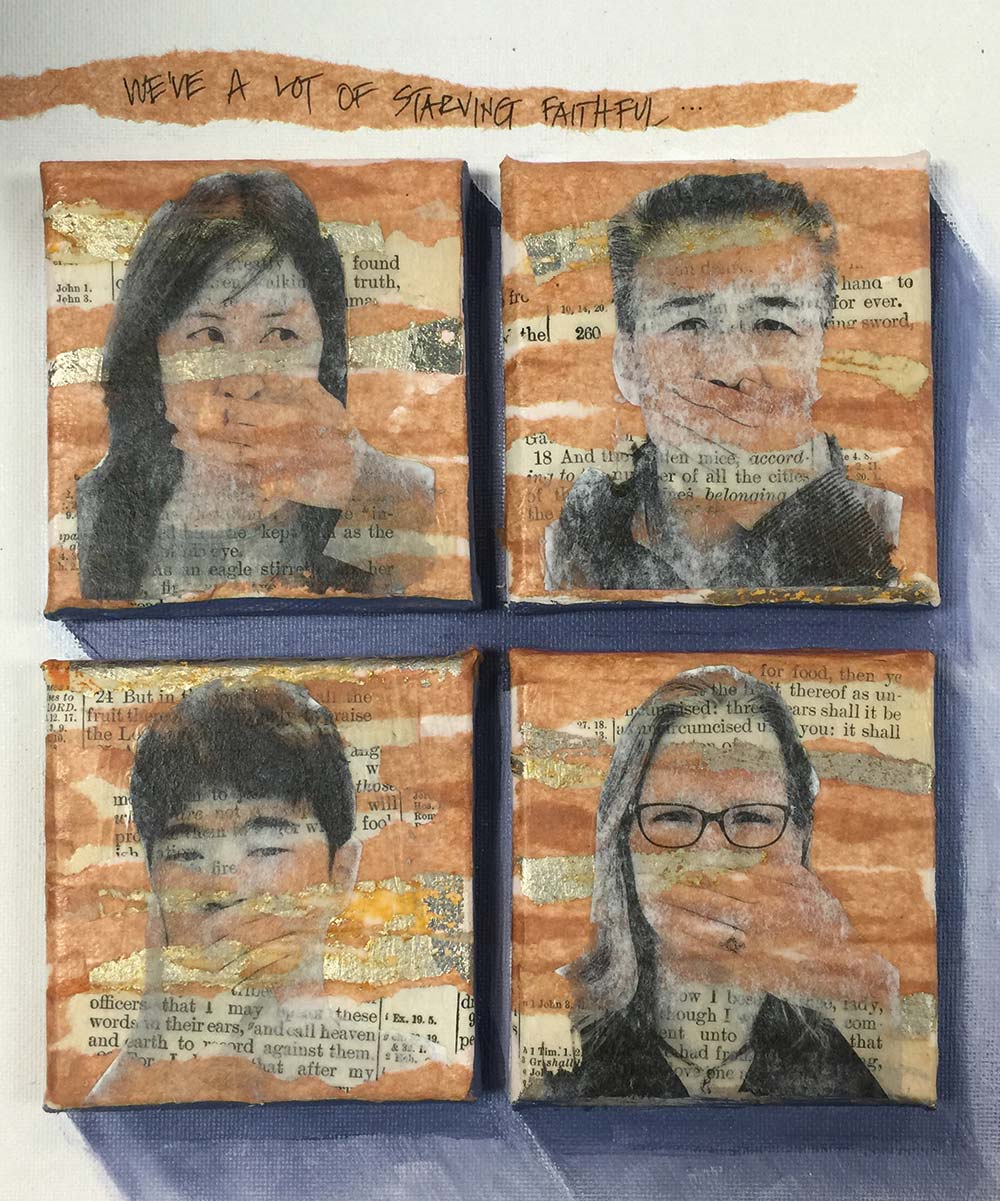

Every one of the 500 seats was filled 10 minutes before the event began. After Bill, our moderator for the evening, finally strode to the center of the stage to open with prayer and explain how this was no longer going to be a debate, he invited Gary, Marian, and me to take our seats onstage.

Upon sitting down, I couldn’t help thinking that I clearly had the most to lose. Gary was already out and proud. Marian was his faithful friend and ardent ally. I represented the traditional view, but having just preached two sermons outlining it, we’d agreed that I wasn’t going to recite it all over again. Furthermore, I believed that God’s Spirit had showed me that I was to lay down my need to be the authority, correct things I didn’t agree with, and emerge at the end with my reputation intact.

In spite of my raging insecurities, the conversation unfolded pretty much according to plan. I asked Gary to share his story with us and he recounted how he’d been attracted to boys while still a toddler and how he had spent most of his life hiding this part of himself, especially in Christian settings. I had him explain how he had come to believe that being gay is exactly who God intended him to be. I also gently challenged some of his gay-affirming statements, but this only made Marian go on about how churches unjustly discriminate against gays.

As the discussion continued, no one had to tell me that my decision not to argue was angering the conservative believers in the crowd. They weren’t just offended by some of what Gary and Marian were saying. They were getting progressively madder at me. I knew they were wondering why I wasn’t vigorously lobbing Scripture grenades every time Gary or Marian uttered things that conservatives believe contradicted the Bible.

In an attempt to appease them, I waited for Gary to take a breath and inserted this well-worn conservative truism: “I believe that the Bible teaches that we’re to love the sinner and not the sin.”

Before I could finish my point, Gary cut me off. He fervently stated that it’s not possible to separate who he is from what he does. Gesturing sharply for emphasis, he declared, “When you hate my life, you hate me. And the Bible actually never says that. What it does say is that we are to love the sinner and hate our own sins. Then maybe when we’ve been sufficiently broken and humbled personally, we would then be humble enough to come alongside fellow sinners and offer them the same grace and mercy that Jesus keeps pouring out on us.”

My first thought was, “You just embarrassed me in front of hundreds of people”, but as the sting of his correction dissipated, I had to admit to myself that I’d never really examined that oft-repeated phrase. As God’s Spirit moved me away from my pride, I felt that I had just learned something that would prove to produce ongoing fruit in the months ahead.

As my reputation continued to take direct hits, the Spirit kept reminding me that, as the senior pastor, I was the most powerful and privileged person on that stage, the one authorized to stand up there to tell people about God and His will. Though I knew I had this authority, I also knew God wanted me to lay it down. Though what I was doing was lost on most of my critics, I began to see that it was clearly worth it.

Since returning to LA as an openly gay person a decade before, Gary hadn’t been back in this sanctuary or on this stage. To see him back where he had led so many vibrant worship services was to witness the Spirit spreading healing ointment on some of his unseemly scars. In my own imperfect way, by extending an olive branch to him (and any other gays or their loved ones in the room) instead of swinging the anticipated cudgel, I helped to reinforce that Jesus loves him — loves all of us sinners — no matter what.

I know that, to this day, there are those who still disagree with my conviction to embody Christ’s civility and humility that night. But the story of the Good Samaritan teaches us that the neighbors God wants us to love are often the people we don’t want sitting, living, or worshiping next to us. Loving undesirable neighbors should always feel uncomfortable and even raise a few eyebrows. Those who’d wanted a heated debate that night left unsettled and upset. What we gave them instead was one tiny example of how Jesus might bridge this huge chasm by using two of the most fundamental elements of our Christian faith — grace and mercy.

After the closing prayer, I was confronted by two fundamentalists from a large church that makes no attempt to hide their condemnation of homosexuals. No matter what I said, they kept warning me that God was going to judge me because, being the pastor, I shouldn’t have allowed any of the “gay-affirming” people to say things that conflicted with the Bible. I finally said, “Look, we’re not having a conversation. You just want to tell me what you believe and where I’m wrong. This is going nowhere.”

I left them and others greeted me, thanking me profusely for doing what I did. Many noted that it was a rare gift to hear the journey of someone like Gary in a church setting. Their reactions were nice to hear and helped me feel good about the evening as the crowd trickled out

Once everyone had left, I went to turn off the lights in the sanctuary. An old friend of Gary’s approached me. By his demeanor, I wasn’t sure of what to expect and I definitely wasn’t prepared for what was about to come out of his mouth. “Stupidity is going to get you killed,” he said.

I was offended. I asked him, “Are you calling me stupid for doing what I did tonight?”

He seemed taken aback. “No,” he quickly replied, “I’m saying that you upset some people tonight and that they’re stupid enough to maybe want to kill you. So don’t accept any invitations to meet with people unless you’re really clear on who they are. Otherwise, there are enough stupid people out there who will want to attack you, maybe even kill you.”

Gary’s friend left and I turned off the lights on what I felt had been a successful evening. I did not quite know what I would need to do going forward, but I knew I had started a fire that would purify me and many others in my sphere of influence, bring healing to some ostracized people, and bring glory to the Lord. I figured things going forward were going to be hot, but never could I have imagined how hot it was about to get. Unbeknownst to all of us, in a few short days the California Supreme Court was going to legalize gay marriage.

Ken Uyeda Fong grew up in Sacramento, CA and graduated with a bachelor’s degree from UC Berkeley. He completed his M.Div. degree in 1981 at Fuller Seminary, the same year he was called as the associate pastor of Evergreen Baptist Church of Los Angeles. He is also now the executive director of Fuller’s Asian American Initiative and assistant professor of Asian American church studies.