Deru kui wa utareru. “The stake that sticks out gets hammered down.”

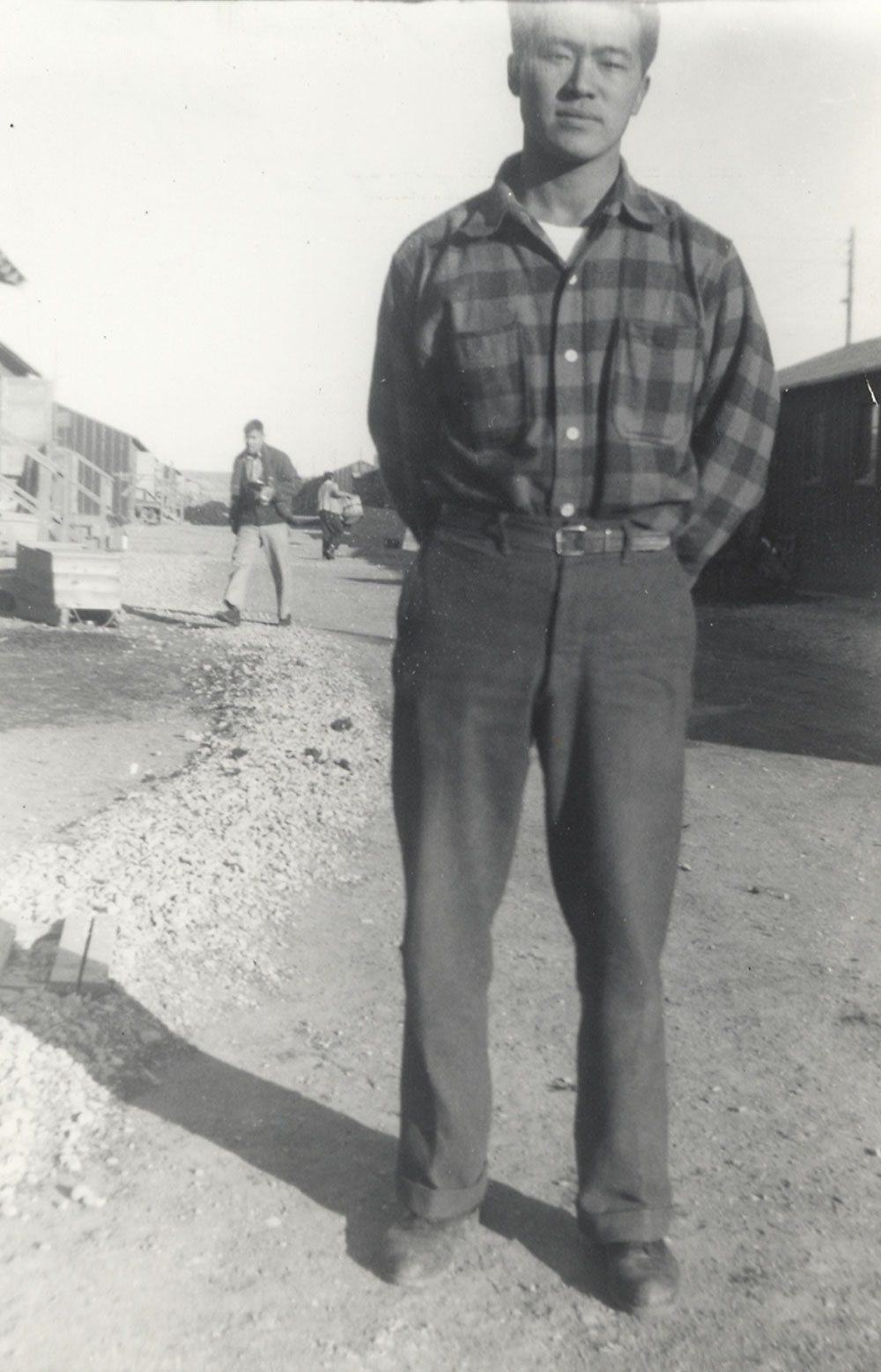

At age 26, Frank Emi (1916-2010) and his family found themselves in Wyoming’s Heart Mountain Relocation Center, over 1,000 miles from their home. Worst of all, the country that had just stripped away Frank’s rights as a citizen was now forcing him to fight on their behalf.

It was February 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had just signed Executive Order 9066, forcing every Japanese American citizen from their homes into internment camps, as a result of the Japanese bombing on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. One hundred twenty thousand Japanese Americans had to leave behind the lives they were building — homes, business, and belongings. Many were torn from their friendships, and racism from neighbors was boiling over.

For people like Frank, the internment camp was hard to forget.

Frank’s daughter Kathy Ito shared, “Heart Mountain was very hot and dusty in the summer, cold and windy in the winter.” Particularly in the first winter, they suffered because of the lack of heating and adequate living spaces. Regardless of the weather, they had to wait outside in lines to go inside the mess hall or to the restrooms located outside.

They were dependent on what the government provided for them, which was often not much, as the government was ill-prepared in their plans for the internment camps. Kathy remembered that her father would salvage whatever wooden boards were left to make furniture as they had no furniture and the government provided only cots as beds. They had only the bare necessities to survive, yet they still followed orders and kept their heads down.

“The camp was just a fact of life. They used to say ‘that was before camp’ or ‘that was after camp’. For the longest time, I thought it was a summer camp — to Yosemite or something. We were young and we heard them talking about it. We didn’t know what it meant until we got older and learned about internment camps.”

A year after being imprisoned, the Japanese Americans had to fill out Leave Clearance Forms — better known as loyalty questionnaires, because two controversial questions were used to determine the loyalty of the Japanese Americans. Question #27 asked whether the men would be willing to serve in the army and #28 asked if they would forswear their allegiance to the emperor of Japan.

With the war going badly, the government needed to recruit men from the internment camps and found support from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which had lobbied for the government to allow Japanese American men to join the war effort. Because there were not enough volunteers, the government began drafting men instead, leading men such as Frank Emi to protest the drafts — it was an injustice to have his citizenship taken away and be asked to fight for the very rights he himself were denied.

Frank Emi joined with his fellow inmates, including protestor Kiyoshi Okamoto, to form the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee. They organized group meetings in the camp to protest the draft as unconstitutional, as the Constitution stated that those held in jail could not be drafted — and they were clearly held as prisoners, unable to freely leave the camp. They were soon followed by a couple hundred men who would not allow themselves to be drafted until their citizenship and freedom were restored.

For his resistance and protests, Emi was later held at the penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas for the majority of the war duration, under charges of conspiracy to violate the Selective Service Act. Frank and the Committee leaders were not eligible for the draft, because they were too old or had children. But they were still being charged with treasonous acts, even though they were technically ineligible for the draft by law, due to their internment status. It was not until the end of the war that President Harry S. Truman gave them all full pardons for their protesting.

While Frank had the support of his entire family for his actions in resisting the draft, they were also affected by his imprisonment. It was particularly difficult for his wife, because she had given birth to their second child, while their family was in Heart Mountain She had to raise two children alone and was only allowed to travel to visit her husband every so often. “She never really expressed that it was a hardship — I never heard her complain once about the situation,” remembered Kathy.

Shikata ga nai. “There’s nothing you can do about the situation, so you shrug your shoulders.”

The majority of the Japanese American population did as they were ordered without loud complaints or arguments. Kathy observed, “The Japanese are very compliant people.” Rather than sticking up for themselves, the Japanese American community went along with the orders. When the drafts came along, Frank and the rest of the protestors earned the scorn of the JACL and the Japanese American community at large, who felt they were unpatriotic and “sticking out like a stake”. This backlash lasted decades after the war had ended.

For them, the church was a strong place of community — a refuge of sorts. It was a place where they didn’t have to talk about these issues. “Sure, some people would say that Frank shouldn’t have made waves, because it affected the community at large, or others would say that he was justified in standing up and ‘sticking out’.”

Despite the lack of support from his community, Frank was inspired to take the stance he did because of the unfairness and injustice of their situation. Though American was a country built on the Constitution, the rights of its citizens were being taken away. Frank pushed against Japanese culture and values by being someone who stuck out and someone who was noticed for the right reasons.

It was easy to target Japanese Americans. Not only did they look different, but their culture and language were different as well. Japanese Americans reacted differently to their Japanese heritage and identity. Older generations held tightly to their Japanese culture, values, and norms. But younger generations struggled with being Japanese during that time, and some even felt embarrassed or ashamed. Whatever their feelings, it was undeniable that acts of injustice were occurring and racism needed to be spoken against.

Koketsu ni irazunba koji wo ezu. “If you do not enter the tiger’s cave, you will not catch its cub.”

Frank once told his children: “Stick up for yourself — someone bosses you around, don’t let them do that. Make sure you say ‘No, I’m not going to put up with that’.” His actions serve as an encouragement for the Asian American community today — not just Japanese Americans — to stand up for more political awareness and engagement. During Reagan’s presidency, the Japanese community demanded a formal apology and $20,000 in reparations for each person sent to the camps. Because they lobbied long and hard, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed, granting the Japanese American community their reparations and apology. On the other hand, it was not until 2002 that the JACL formally apologized to the resisters and made steps toward reconciliation.

It is not by the actions of one person, but rather many individuals who bring change. Frank Emi did not stand up against these injustices alone, but was backed by many others with the same cause. Kathy said, “You need to stand up for yourself, but you also have to realize that everybody is not just an individual. There is a group dynamic here that you have to also include in your decision.

“My dad stood up in a time when it was unpopular to ‘stick out’. His life lessons have made their mark on me. It is so important that the younger generation know his story. We can’t be heard if we don’t stick out.”

Credit: Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, Frank Emi Papers

Rachel Tien is an alumna of Biola Univeristy with a background in Christian Ministries concentrating on family ministry. She is currently pursuing a master's degree in Intercultural Theology & Interreligious Studies at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland while also taking time to explore wherever her feet may lead her in the world.

Kathy Ito is the daughter of Frank Emi. She grew up in Los Angeles and now resides in Camarillo, CA. She worked as a Los Angeles Uni ed School District school teacher and in the administration offices, and is now happily retired. Kathy enjoys hiking, fishing, and having fun with her three grandchildren.