Escapist from the Lao Civil War. Refugee in Thailand. Immigrant to the United States. This is the story of why Chiraphone Khamphouvong dedicates her life to meeting the physical and spiritual needs of people around the world.

My name is a Sanskrit name given to me by my father's Buddhist monk teacher. The first part, "Chira", means eternal and everlasting. The second part, "phone", means blessings. The meaning of my name, "eternal and everlasting blessings", has shaped both my upbringing and my life today.

I was born in a small village called Sayaboury in Lao People's Democratic Republic (PDR) of Southeast Asia during the time of the civil war, when the Communist Party was gaining power. My family of 12 escaped and lived as refugees in Thailand before eventually migrating to the United States. But my story begins before I was born.

My mother is from Southern Lao and came from a humble village background. Her marriage with my father was arranged three days after they met, and their arranged marriage grew into a loyal and unwavering marriage of 50 years, raising 10 kids and surviving a civil war together.

My father was a Buddhist monk for 14 years and also studied in the United States. He reached the "Maha" or "great" status and worked with the United States Agency of International Development (USAID) with the inspiration to "do more for his people outside the temple." My father served in diplomacy and community development for 14 years, spoke four languages proficiently, and became admired by many as the top liaison working with the U.S. Embassy and the government in Lao. Because of his position with the USAID, my father was able to provide our family with a life of honor and prestige. We lived comfortably — we had no physical needs, were well respected in our village of Sayaboury, and even owned our own elephants.

But our lives took a turn for the worse in 1974 and 1975. The American government was gradually phased out, and my father was the only USAID representative left in the region. The Lao communists soon took over Sayaboury. And as they did with other villages they occupied, they killed several of our villagers.

In October of 1975, my father was labeled as an "imperialist slave" and was taken by the communists to a "re-education" prison at Muang Ngai for three and a half years. There, he was put to do hard manual labor — clearing the jungle, cutting bamboo, and constructing sawmills. He knew the only way to survive this time of torture and imprisonment was to act happy and obediently succumb to what was demanded of him. But my father also knew that the life he knew in Lao was over. He was faced with two options: to either escape, or to die in his homeland with his family.

The Lao Civil War was a time of fear and instability. But I, being the sixth of 10 children — eight biological and two adopted cousins whose parents had passed from wartime illness — was largely shielded from much of this turmoil. I was 5 years old, and unaware of much of the tension around me. I remember happily making mud cookies in front of our large, Western-style home in Sayaboury Village. There were two fresh water wells in the village; one was in the village, and one was in our yard. Our doors were always open to strangers, friends, and family, and I grew up without lacking any love or care.

As a 5-year-old, I was unaware how much my mother suffered in my father's four-year absence. When my father was taken away to prison, she suddenly became a single mother caring for 10 children. She endured the struggle to manage the family's well-being and to keep us alive. My mother proved her strength and commitment to provide for her children by diligently working in the field, as well as taking up various business trades.

In 1979, my father was released from the prison camp on good behavior. After his release, he made contact with Jon and Carol Wells, his former American International Development counterparts. They had served in Lao for three and a half years with the International Voluntary Service in Sayaboury in 1967 and had offered our family a sponsorship if we "ever came out". The release and the promise of friendship was the encouragement for my father to escape.

In 1980, my family left all of our possessions and loved ones behind so as to not raise suspicions. Not even our neighbors or grandparents knew of our plan to escape. We were running away from the life we had to save our lives. My father and eldest sister escaped to Thailand first. With the help of a family friend, they crossed the border into Thailand. My eldest brother led my mother and the other eight children from one village to the next, aiming to cross the Mekong River that separates Lao and Thailand. For the younger children like me, this was nothing more than another family trip. What we didn't know was this was actually a matter of life and death. I recall it raining a lot as we walked through bamboo jungles and rice fields. To this day, the smell of glutinous wet rice paddies, dark thick clay, and the sound of bamboo stalks rustling in the wind takes me back to that journey my family made when I was just an adventurous 5-year-old.

Our plan was to enter Thailand by crossing the river near Vientiane, Lao' capital city. But when we got there, the river was too high to cross and we had to reroute to Kene Thao, extending our journey by 12 hours. Once we reached the village, we planned to send two family members across the river each night. My older sister, the third born, and I were the first to cross. My mother gave my sister enough money to use for the safe house and food for one night and day. We were placed in a small wooden fishing boat, covered with well-used burlap, and told to lie completely still as we waited for the communist soldier to change shifts for the night. When we heard a bicycle bell ring, we knew this was the cue for the fishermen to smuggle us across the river. Little 5-year-old me just thought of this as a different kind of adventure and had no idea how worried my mother and older siblings were, frightened that one of us might get shot or killed.

Thankfully, my entire family made it to Thailand without any harm. We were reunited with my father and eldest sister at the Nong Khai refugee camp, where about 35,000 other refugees lived. It's estimated that 300,000 Lao escaped in a 10-year span during that time, many of them also fleeing for their lives. My family was assigned to a 12-foot-by-12-foot stall in a refugee bamboo resettlement block, but we didn't mind the crammed quarters — what mattered was that we were safe, and that we were together.

While my family was waiting for the U.S. Embassy paperwork to be processed with the sponsorship of Jon and Carol Wells, we made the most of our stateless status. My father was able to find work as a community organizer and translator with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), International Rescue Committee (IRC), and American Friends Service Committee. My father worked to plant trees, a garden, and raise chickens to develop sustainable resources. My mother continued to keep the family healthy and together, and my older siblings attended English schools as part of their cultural orientation to prepare for our migration to the United States.

At the refugee camp, I couldn't believe that not everyone was Lao. I couldn't understand how they could have the same hair and eye color as us, yet speak a foreign language. My worldview was in culture shock and it was my first "fish don't know water until it is out of water" moment. My family and I knew we would be migrating to the U.S. in a matter of time, we focused on learning the English language, managing limited food rations, staying healthy, and being united as a family. The refugee camp was a place of simplicity. Everyone had a story. Everyone left their home and loved ones for a better life. Everyone wanted to find hope in each other's struggle, suffering, and pain.

In Sanskrit, "Pra-jiaow" is God the god. "Pra-Yesu" is God the Jesus. My family was introduced to God the Jesus for the first time at Nong Khai refugee camp. That was the first time I heard the name "Pra-Yesu." My family listened as the Christian missionaries taught Bible lessons through storytelling and worship; many in the camp felt a sense of belonging and became involved in the missionary workers' ministry and claimed a conversion from Buddhism to Christianity during that time. But to be Lao is to be Buddhist. When I was first introduced to "Pra-Yesu", the name entered my ears, but took longer to fully resonate in my heart. My family's time at Nong Khai refugee camp was the beginning of our spiritual journey of Christianity as we prepared to be relocated to the United States of America.

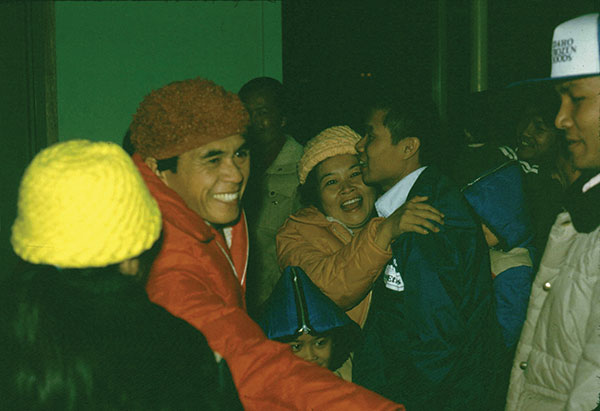

At the end of 1981, almost having spent two years in the refugee camp, my family was notified that the United States of America had granted us political asylum. So in January 10, 1982, we migrated from the tropical lands of Southeast Asian to the cold, barren farmland of Idaho. When we arrived, we were greeted with six feet of snow and icy roads, but thanks to World Relief, a refugee settlement agency, we were warmly welcomed by the Wells family and the Baptist Church of Buhl, Idaho.

Everything was new and foreign for our family in America. The freezing weather. The white, sliced Wonder Bread. Biting into an apple, not a mango. The different colors of people's hair and eyes. The elongated nose and the height of everyone compared to the Lao people. The different languages. We all had to start over. My father was able to find work at a fish cannery. It was a culture shock, but looking back now, it was a blessed and gracious time. We took the yellow bus to school every morning, learned new English words, and ate American food during lunch time.

God's grace can be seen all throughout my family's journey of coming to America. Things were quite different from our life of affluence and prestige back in Lao; we all lived in a one-bedroom, one-bathroom house — my parents, youngest baby brother, and four girls slept in the bedroom together, while the other five boys slept in the living room. But we were all grateful to be alive. We did life together in the simple farmhouse for a year and a half. We were safe, we were together, we were blessed.

Chiraphone Khamphouvong has served as the director of partnerships and resource development with World Relief in Cambodia since 2014. As a Lao civil war escapist, a refugee in Thailand, and an immigrant to the U.S. in 1982, she is devoted to a life of holistic international service to meet the physical and spiritual needs of the human family worldwide.