After 31 countries of service and work travel, 32 years of being settled as an escapist, refugee, and immigrant, Chiraphone returns to the Southeast Asia region.

At the age of 15, in 1989, after fully surrendering to Christ, I became very zealous with life. I wanted to live a life that embraced all cultures, customs, and traditions; a life where loving God and loving others was the focal point. After my conversion, I experienced a sense of social and cultural freedom. I felt full of life and possibilities — freedom in Christ through the knowledge that I was a new creation in Him. I had one goal Be out in the world and serve others because of my new transformational faith.

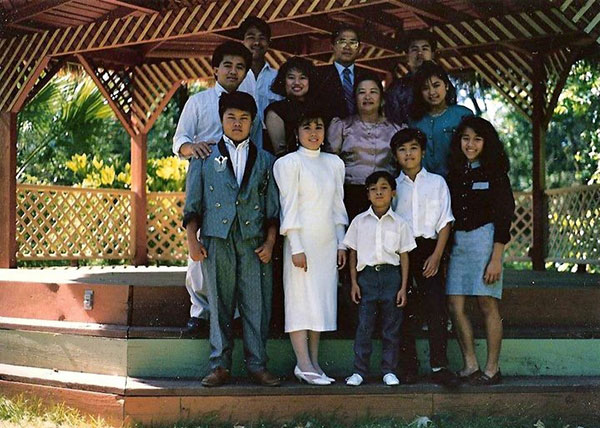

When I was settling in the rich community of Chico, California, God knew I needed the extra grace and mercy of my beloved community. I gained countless extended moms, teachers, leaders, and mentors who constantly gave me guidance. I received support from my grade school best friends and their families, who received me as their own. They, along with my local church, provided ways for me to grow and be supported in my navigation of self-identity and balance of being in both the Lao and the American culture, as well as straddling Buddhist traditions and exploring more of the Christian faith.

At Marigold Elementary School, 10-year-old me with long, braided hair was very different from what my Caucasian classmates expected in the new student. Although I only had two and a half years learning American culture and the English language, everything was still quite foreign to me.

In junior high at the age of 15, I experienced my first service to others. The leadership team of my youth group took a bunch of knuckleheads down to Los Angeles to help and do home projects with socially and economically struggling widows and single moms. Some of us assisted a neglected elderly woman by cleaning her yard and fixing minor things around her home — but it really was more about spending time together. She was somebody: a daughter, a sister, a wife, a mother, an auntie, a grandma, and a neighbor. Though as adolescents we may have been more of a nuisance to our leaders as well as those whom we were "serving", we were sharing life together. I learned then that making the world a better place meant connecting with each other as human beings, and that our differences have nothing on our human similarities of love, life, pain, grief, and hope.

The year before my first international service with the Peace Corps in 1998, I felt convicted to go to my birthplace in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. I had been naturalized and became a U.S. citizen, so it was more secure for me to make the journey home. But I was not returning to the motherland alone; it was a family's sojourn back. I was representing my family, my kin.

After a week of a mission prayer trip to Thailand, I went to Vientiane, the capital city of Lao PDR. I distinctly remember I wanted to be Lao returning to my homeland, so I put on my sinh (a traditional Lao silk skirt) at the Bangkok airport so that I could begin the journey home. When we landed, the officials adorned with heavy military rifles interrogated me because they recognized my family name, Khamphouvong. Although I was uncertain of what they would do, with a non-negotiable tone and face, I said, "I am a Lao-born U.S. citizen visiting her birthland." It was not a warm and light welcome, yet with some statements of "do's and don'ts" in Lao, I was permitted through immigration and exited the airport. I was thankful for the reminder that Lao PDR is still a private state, and that I should be on guard with how I interact with such a social system. In the Southeast Asian midday heat and humidity, I was greeted by more than 20 family members, many of whom I had never before met, but who looked like me! I felt an overwhelming sense of joy and elation as the family's disconnect over several years was now repaired.

In 1997, I did not see McDonald's or Coca-Cola products, but the Lao females wore the traditional Lao sinh — I was happy about our preservation from globalization.

It was powerful to experience my birth village — a beautiful site of cultural beauty. I had the opportunity to visit the home that I was born in — to see the exact steps that I was born on, because according to my mother, I just couldn't wait to be born. I met more family members and everyone offered their homes and meals. Like many underdeveloped or developing parts of the world, subsistence farming is widely practiced. I had the opportunity to visit one of the sticky rice fields as it was harvesting season, and was able to cut a portion of the yellow, matured rice stalks. As I was riding on the back of my nephew's scooter in Sayaboury, a man was riding on an elephant down the road! I had to stop my nephew to admire such beauty of the magnificent land mammal. Indeed, I was able to experience firsthand a domesticated elephant as Lao is also known as Lan Xang, "Land of a Million Elephants". All in all, who was I to embark on a life of international service without experiencing my own Lao heritage and roots?

My first overseas experience as a Peace Corps volunteer took place in South Africa from January 1998 to 2000 as an Education and Community Resource Worker. About eight years after being prophesied over at the age of 15, I was able to live and serve my life's dream. South Africa had just opened its doors to external development agencies post-apartheid, following the 46 years during which 10 percent of the nation's population received white privileges over the Black, Indian, and Colored (a term to describe South Africa's mixed races) demographic.

I again embarked on a new frontier as a now Lao American, learning to speak Zulu as my sixth language and living with a Zulu family for the two years of service. I stayed with Mama Lungi, a single mother of one boy who also took in her sister's son. Of course, per tradition for a Zulu family and the magnitude of their hospitality, extended family and guests were always present, which took me a while to learn who was who and how I fit within the family and social structures. I was also given the Zulu name of Jabulile, meaning "one who is happy, content, free-spirited", or as I would like to add, a little crazy — crazy to think that in a world of such evil, mess, and human hatred, the hope, freedom, love, and grace of God can still have dominion.

God has always opened my doors for me. He has always gone before me and is with me. I refer to it as God's favor in my life. With my service in South Africa, I learned more in depth about humanity and grace, and obtained the skillsets to facilitate the process of collective learning and development for the greater good for all people, every tongue, tribe, and nation.

As a worker with 28 schools (the majority of which were Zulu schools in the township of Vukuzakhe, Mpumalanga) and 600 educators, I learned more about sustainable holistic development and the spirit of ubuntu, which is also conveyed through the African proverb of "Umuntu, umuntu ngabantu." It means a person is a person because of others. Basically, my humanity is your humanity. I also learned about simunye, meaning "We are one". Simunye is so vital because South Africa is still healing and reconciling its past 46 years of apartheid.

A focal point of my work ethic and value was refined in South Africa. I recognized the influence I had with people, and I wanted to be a part of making this world a better place for all people, especially those who are in underrepresented people groups. All of my previous family background, studies, and collegiate extracurricular groups had started my process of this embraced life purpose and identity. In South Africa, I had the privilege to live it. From leadership development entities like Student Government Association and Multi-Ethnic Student Alliance, along with attending various multi-cultural, international conferences like Urbana 1996, the many great women leaders and mothers who mentored me with great wisdom guided me along in my journey of service. It was a true ubuntu process for me.

In South Africa, I learned about allowing the majority and the collective to be at the forefront in owning the process and outcome of holistic development. I learned in a leadership class from Henri Nouwen's book "In the Name of Jesus" that even Jesus had to follow God the Father before He ministered and led the disciples. With my Zulu, Indian, and Afrikaner friends, I learned to move at their pace as they made decisions to develop from within; and as a short-term outsider, I had to learn to listen more than speak. It took about nine months for my counterparts to be assured that I was choosing to live, learn, and serve amongst them. Once they trusted me, we were able to establish a more collaborative work environment. The following 15 months allowed a more in-depth, positive impact for me as a Lao American, who is not Black or a white American, to have a neutral face as a medium of development.

Again, this is a reminder of God's favor in the undeniable ethnic card God gave me in working with a post-apartheid public school and community-organizing social climate.

Currently, my home in the world is Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where I've been serving as World Relief Cambodia's Director of Partnership and Resource Development since July 2014. God's story has come full circle across 31 countries of service and work travel. After 32 years of being settled as an escapist, refugee, and immigrant to the U.S., God has brought me back to the Southeast Asia region. Among the approximate 140 staff members with WRC, only two of us are expatriates, and I remain as the only non-Khmer staff.

Cambodia is still healing from its scarred past of the Pol Pot regime and the Khmer Rouge genocide. About one-fourth of the population was killed from 1975 to 1979. Similar to what I've seen in my South Africa service, Cambodia is a nation that is in the process of transformation. The cultural similarities between Lao and Khmer have overlaps, however, not as much as Lao and Thai. In Southeast Asia, the saying "Same same but different" is very reflective of how much our people groups have in common yet are very distinctive in our cultures and traditions. Because about 96 percent of the population of Cambodia identifies as Theravada Buddhist, I am able to relate and navigate instinctively with the culture and customs.

Each and every Khmer person was directly or indirectly affected by the Khmer Rouge genocide. Many have family, neighbors, and friends who were killed or escaped. I can relate to all of those experiences and am also able to steward the grace of mercy back to any people group, country, or region of the world as the Lord directs. Every day, it is good to be alive!

The work of WRC is important because it is about God's people working together to meet the physical and spiritual needs of the vulnerable, the harmed, and the forgotten. Similar to my role with Peace Corps South Africa, it is important for a "we" value and concept, yet allowing and making way for national and local leaders to emerge. Bridging the links of mutual and dignified mission and ministry together honors and glorifies God. I feel very honored and humbled that I get to serve in this capacity with WRC. I am confident that my Lao ethnicity has been an advantage in serving in various contexts across the globe. God's favor in preparing my heart and mind, blessing me physically with mobility and health, providing the global competencies along with innumerable mentors, mentees, and leaders, have all been a part of God's story of my life thus far. I continue to anticipate greatness in the years to come! I am rich beyond description. I am in deep gratitude.

I have learned several life lessons about leadership, global mission, and development. I have learned that leadership is lonely and, most of the time, it is very hard and messy work. It can get really ugly when pride and discrimination are a part of the equation. In leadership, the unseen valley low experiences surpass the recognizable mountain top experiences. Therefore, I've learned to give leadership away. As mentors and leaders pour into our lives, we ought to invest in the lives within our sphere of influence. It is part of God's purpose in our lives to embrace our ethnicity and family heritage. If we do not value and celebrate the imago Dei in ourselves and others, we are slapping God, our Creator, in the face. I've seen damage by many insecure young adults who allow social dictations to negatively affect their lives. Learn to love God, love yourself, and love others.

We live in a very unloving and broken world, yet there is hope all around us to capture. Obedience to the Lord is about living life to the fullest — a part of my ongoing "edu-ma-cation" — live your life dash. We all have a birth date. We all will have a death date. That dash in the middle is what will speak for our lives on Earth to God and to others. May the Kingdom of God be sought and found locally and internationally as a testament of God's love for each of us — where much has been given, much is required. (Luke 12:48)

Chiraphone Khamphouvong has served as the director of partnerships and resource development with World Relief in Cambodia since 2014. As a Lao civil war escapist, a refugee in Thailand, and an immigrant to the U.S. in 1982, she is devoted to a life of holistic international service to meet the physical and spiritual needs of the human family worldwide.